Research-Supported PBL Practices

At one New Tech Network high school, strategies backed by research make project-based learning effective and engaging for teachers and students.

At Manor New Technology High School in Manor, Texas, several research-based practices interact to promote successful inquiry-based learning:

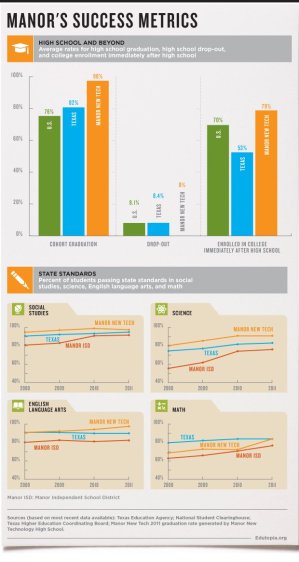

Manor New Tech is part of the New Tech Network, a nonprofit that works with schools and districts around the country providing services and support to help reform learning through project-based learning (PBL). Since opening its doors in fall 2007, the school has achieved several notable accomplishments:

- It has graduated two classes with an average annual graduation rate of 98 percent.

- All 39 students in the first senior class graduated, and 95 percent of the 74 students in the class of 2011 graduated. Those who did not graduate are continuing to work on getting their diplomas.

- On average, 96 percent of students in the first two classes (100 percent of those who graduated) were admitted to college, and over 50 percent of those admitted were first-generation college students.

- Currently, 79 percent of Manor New Tech graduates have enrolled in a two- or four-year college immediately after high school, according to the National Student Clearinghouse, thus surpassing the national rate of 70 percent.

- The school has outperformed the state of Texas and Manor Independent School District in the percentage of students passing state standards in three of the four subjects tested: science, social studies, and reading/English language arts.

Collaborative Project-Based Learning

When implemented well, PBL has been shown to develop students' critical thinking skills, improve long-term retention of content learned, and increase students' and teachers' satisfaction with learning experiences (see Ravitz, 2009, for a review). Students at Manor New Tech typically complete nearly 200 projects over the course of their high school experience, with each project lasting about two to four weeks. (See our article "A Step-by-Step Guide to the Best Projects" for more details on Manor's PBL process or watch the video.)

In designing projects, teachers spend significant time developing a driving question, which forms the backbone of the project and helps to engage student learning (Blumenfeld, Soloway, Marx, Krajcik, Guzdial and Palincsar, 1991). An example of a driving question is, "How can we use mathematics to design and use a Dobsonian telescope?" Teachers at Manor New Tech start with the end goal in mind and avoid canned projects to ensure relevance to their students. As a general rule, the driving questions at Manor New Tech must be mapped to state standards and cover a sufficient number of them to warrant the time spent on the project. In accordance with research on effective problem-based learning designs (Hung, 2009), teachers at Manor New Tech design projects so that learning the content defined by the state standards is necessary in order to successfully complete the project.

At the start of each project, students receive a detailed assessment rubric that outlines the state standards the project covers and provides explanations of how performance will be assessed. Providing a rubric for students has been shown to promote students' time-on-task and content-related discussion (Barron and Darling-Hammond, 2008). The rubric often includes time lines and information on essential elements of successful final products (for example, if a report may be produced as a podcast rather than a paper, the rubric specifies minimum length for the podcast). After students have received the assignment, teachers ask them to determine what content they know and what they need to know. The need-to-know lists are reviewed as a class, and any questions are clarified. Students are prone to ask questions about project logistics (e.g., Can we use music? When is it due? How many grades will we get?), but by adding a content section to the list of knows and need-to-knows, students are more likely to ask questions about content, a practice that is at the heart of inquiry-based learning (Yañez, Schneider and Leach, 2009).

Well over a thousand studies support the impacts of collaborative learning on improving student achievement and promoting positive peer relationships across group lines (Johnson and Johnson, 2009). The way that teachers support successful collaboration is likely an important ingredient in Manor New Tech's success. Students are assigned to groups of three or four, and the first group project meeting begins with groups creating contracts that establish shared norms or expectations for behavior (e.g., being on time, not criticizing each other's ideas, etc.). Building individual accountability into the project process helps to promote successful student collaboration (Slavin, 1996). If a student is not fulfilling his or her portion of the project, it is the responsibility of team members to bring this to the teacher's attention, being specific about the responsibilities that are not being completed. Team members can be fired, which means that the fired student must complete the project on his or her own, although this occurs infrequently at Manor New Tech.

Once a project is under way, teachers' roles shift to advisers, coaches, and evaluators, scaffolding students' success with ongoing and diverse assessments and giving benchmark grades as key stages of the project are completed. Importantly, teachers adjust the project in response to student input, several citing Angelo and Cross's Classroom Assessment Techniques as a frequent reference (Angelo and Cross, 1993; Dickinson and Summers, 2010). During in-class presentations, which occur throughout the project process, students provide feedback to each other using the "I like/I wonder/next steps" format (i.e., statements should begin with "I like…" or "I wonder…" or provide suggestions for next steps).

In addition to the content objectives, which are based on state standards, Manor has six learning outcomes that are assessed in every project: written communication, oral communication, collaboration, critical thinking, work ethic, and technology literacy. Two additional learning outcomes -- numeracy and global awareness/community engagement -- each must be assessed in at least one project per semester. By providing clear learning goals at the start of each project and ongoing and diverse assessments with frequent feedback, Manor New Tech creates an environment for effective inquiry-based learning (Barron and Darling-Hammond, 2008).

Supporting Teachers' Development and Leadership

Professional development has been shown to help teachers implement PBL successfully (Toolin, 2004; Ravitz, Hixson, English and Mergendoller, 2012). Manor New Tech has instituted several systems that effectively support teachers in leading project-based learning throughout the project cycle:

- Professional Development Mondays: Once a week, the school employs a one- to two-hour delayed start for students so staff can engage in a range of professional development meetings, including faculty-wide meetings and leadership committees.

- Critical Friends: This peer-evaluation protocol (also used by students to evaluate each other's projects) often takes place on Mondays and provides a supportive meeting space in which teachers receive feedback on project designs and suggestions for how to adapt tactics as projects progress.

- Teaching Advancement Program: TAP provides time and compensation for teachers to take on extra responsibilities and to mentor other teachers. Master teachers are always on call to provide assistance and mentorship to their peers, and many new teachers cite the master teachers as critical to their success and confidence (E3 Alliance, 2009).

- Project Lead The Way provides STEM curriculum, teacher training, professional learning communities, and business partnerships that enhance the professional relevance of PBL and work-based learning opportunities. Manor New Tech students follow this STEM curricular program, which requires all students to take two courses in engineering (Engineering Design and Principles of Engineering).

- Summer professional development: Each year, all Manor New Tech teachers participate in the New Tech Network's summer training institute. In addition, Manor New Tech hosts the Think Forward Institute, a training workshop for teachers and administrators from Texas and beyond on how to lead PBL successfully. Manor teachers report that engaging in professional learning communities and teaching others about their methods helps them reflect upon and refine what they have learned over the course of the year.

- UTeach enables pre-service education students at the University of Texas to gain experience in PBL instruction at Manor New Tech, as well as at other inquiry-based high schools. A substantial number of teachers at Manor New Tech have been recruited through the UTeach program (International Center for Leadership in Education, 2010).

- Team-teaching and one-on-one professional development coaching are regularly supported at Manor New Tech.

This system of supports helps teachers to design and lead engaging, rigorous projects at Manor New Tech. In addition, the school encourages creativity in project designs and in the approaches that students can take to complete their projects. Providing teachers with greater autonomy over their work, in the context of accountability arrangements, along with professional development, have been shown to promote the success of teachers and students (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2011).

Technology Integration

In general, technology works best when it facilitates learning and activities that would occur without the technology, while extending the time, place, and pace at which they can occur (Naidu, 2008). An analysis by the U.S. Department of Education (Means et al., 2010) also found that blended learning environments are more effective than either online learning or face-to-face learning alone. To blend face-to-face and online learning, Manor New Tech uses New Tech Network's proprietary Echo platform, which integrates Google Apps for Education, to support project collaboration and facilitate communication among parents, students, and teachers. The platform includes the following features:

- Grade tracking: The platform's online grade management tools display student progress on multiple learning outcomes such as the state content standards, written and oral communication, collaboration, critical thinking, work ethic, and technology literacy. The online system provides a comprehensive indicator across grade levels and classes that helps teachers, parents, and students see individual student strengths and weaknesses on a daily real-time basis, enabling teachers to coach students accordingly.

- Instruction and training resources: Resources include New Tech Network's guidelines and tools, teacher-created documents (e.g., rubrics, scaffolding activities), and professional development materials tied to PBL.

- Library: The library is a collection of high-quality projects developed by New Tech Network teachers that are available for immediate teacher use.

- Student journals: Journals facilitate student reflection, help teachers check students' progress, and ensure that students are on course and understand the content.

- Discussion forums: Students and teachers can instantly share ideas and resources.

- Agendas: Daily agendas are linked to project tasks, reinforcing collaboration and school culture.

- Evaluation tools: Tools facilitate peer feedback and help students evaluate projects or group collaborations, as well as enable teachers to track behavior and reward positive student behavior accordingly.

The Scalability of the New Tech Model

High school reform researchers consistently find that immediate positive outcomes are more likely when launching a brand-new school like Manor New Tech, as compared to redesigning underperforming schools (National Evaluation of High School Transformation, 2006; cited in E3 Alliance, 2009). New Tech Network has grown rapidly from 16 schools in the 2006-07 academic year, to 42 schools in 2009-10, to 85 schools in 16 states in 2011-12 (New Tech Network Outcomes, 2012). New Tech's internal evaluation data indicates promising evidence that its model has replicated successfully, with an average four-year cohort graduation rate of 86 percent, an average dropout rate of less than 3 percent, and a college enrollment rate of 67 percent immediately following high school graduation (New Tech Network Outcomes, April 2012; New Tech data 2012).

However, the scalability of the New Tech Network model remains an open question. Can New Tech maintain the quality of the services it provides as it scales nationally? In addition, will New Tech's model work for schools that lack the infrastructure to support systematic professional development around project-based learning and 1:1 computing?

An additional factor that may also account for Manor New Tech's success is that students must apply to attend. Even though Manor New Tech uses a blind lottery system, all students who apply are likely to be more motivated to succeed in school.

Bibliography

Angelo, T.A. and Cross, P.C. (1993). Classroom Assessment Techniques: A Handbook for College Teachers (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Barron, B., and Darling-Hammond, L. (2008). Teaching for Meaningful Learning: A Review of Research on Inquiry-Based and Cooperative Learning.

Blumenfeld, P. C., Soloway, E., Marx, R. W., Krajcik, J. S., Guzdial, M. and Palincsar, A. (1991). Motivating Project-Based Learning: Sustaining the Doing, Supporting the Learning. Educational Psychologist, 26 (3 and 4), 369-398.

Dickinson, G., and Summers, E.J. (2010). Understanding Proficiency in Project-Based Instruction: Interlinking the Perceptions and Experiences of Preservice and In-service Teachers and their Students; A synthesis report prepared for Manor New Technology High School, Manor, TX. Texas State University-San Marcos.

E3 Alliance. (2009). Case Study of Manor New Tech High School: Promising Practices for Comprehensive High Schools.

Hung, W. (2009). The 9-Step Problem Design Process for Problem-Based Learning: Application of the 3C3R Model. Educational Research Review, 4, 118-141.

International Center for Leadership in Education. (2010). Case Study of Manor New Technology High School, Manor, Texas. Model Schools Conference, June 2010, Orlando, FL.

Johnson, D. W. and Johnson, R. T. (2009). An Educational Psychology Success Story: Social Interdependence Theory and Cooperative Learning. Educational Researcher, 38 (5), 365-379.

Means, B., Toyama, Y., Murphy, R., Bakia, M., and Jones, K. (2010). Evaluation of Evidence-Based Practices in Online Learning: A Meta-Analysis and Review of Online Learning Studies. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education.

Naidu, S. (2008). Enabling Time, Pace, and Place Independence. In J.M. Spector, M.D. Merrill, J.J.G. Van Merriënboer, and M.P. Driscoll (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology (3rd ed.), (259-268). New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2011). Building a High-Quality Teaching Profession: Lessons from around the World. OECD Publishing, Paris.

Ravitz, Jason (2009). Introduction: Summarizing Findings and Looking Ahead to a New Generation of PBL Research. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-based Learning, 3 (1), Article 2.

Ravitz, J., Hixson, N., English, M., and Mergendoller, J. (2012). Using PBL to Teach 21st Century Skills: Findings from a Statewide Initiative in West Virginia. Paper presented at Annual Meetings of the American Educational Research Association. Vancouver, BC. April 16, 2012.

Slavin, R. E. (1996). Research on Cooperative Learning and Achievement: What We Know, What We Need to Know. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 21, 43-69.

Toolin, R.E. (2010). Striking a Balance Between Innovation and Standards: A Study of Teachers Implementing Project-Based Approaches to Teaching Science. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 13 (2).

Yañez, D., Schneider, C. L., Leach, L. F. (2009). Summary of Selected Findings from a Case Study of Manor New Technology High School in the Manor Independent School District, Manor, Texas. Charles A. Dana Center at The University of Texas at Austin.

What do you think about this Schools That Work story? We'd love to hear from you!

Tweet your answer to @edutopia.

Manor New Technology High School

Enrollment

345 | Public, SuburbanPer Pupil Expenditures

$5488 School • $6909 District • $7494 StateFree / Reduced Lunch

54%DEMOGRAPHICS:

5% English language learners

4% Special needs