Talking in Class

Strategies for developing confident speakers who can share their thoughts and learning.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Overview

"What makes me enjoy talking the most," explains Milo, a Year 3 student, "is that everybody’s listened to you, and you’re part of the world, and you feel respected and important."

Oracy -- the ability to speak well -- is a core pedagogy at School 21, a London-based public school.

"Speaking is a huge priority," stresses Amy Gaunt, a Year 3 teacher. "It's one of the biggest indicators of success later in life. It's important in terms of their employability as they get older. It's important in terms of wellbeing. If children aren't able to express themselves and communicate how they're feeling, they're not going to be able to be successful members of society."

Oracy is taught during assemblies and wellbeing classes, but "it's embedded into every single lesson," says Gaunt. Students use oracy techniques in the classroom, every day, in every lesson -- guided by their oracy framework -- to discuss their ideas about Ancient Greece, problem solving, and explaining their learning in maths.

From forming different groupings to using talking points, learn how you can integrate strategies for effective talk in your classroom.

How It's Done

Embedding Oracy Into Your Classroom (It's Already Happening)

The first step in embedding oracy into your classroom is accepting that it already happens -- your students talk a lot, and you can leverage that, suggests Gaunt. "You start from the idea that talking isn't an extra thing," she advises. "It's children discussing ideas with each other and coming up with their own conclusions. Talk supports thinking, and that means it supports learning."

Teaching oracy means putting more intention behind how you guide and organize your students' talk. When they gather for group work or discussions, give them talking guidelines, roles, and tools. For example, sentence stems are starting phrases that help them complete their thinking in a full sentence and add intention to how they form their thoughts and communicate their learning.

Create Discussion Guidelines With Your Students

Creating discussion guidelines with your students is a great place to start implementing oracy in your classroom. "Once you've got them, it encourages you to include a lot more discussion within your lessons, and it also gives you a framework for those discussions," says Gaunt. "Having a clear set of guidelines makes sure that discussion is focused and that it has good learning outcomes, as well."

Create your discussion guidelines with your students. Show them examples of what good and bad discussion looks like. You can show them a prerecorded video, or model for them with another educator. "Through looking at the differences between good and bad discussion, we were able to say, 'These are the five or six key things that we think make a really good discussion.' And they become our discussion guidelines," says Gaunt.

Here are a few of the discussion guidelines that School 21 students have created:

- Always respect each other's ideas.

- Be prepared to change your mind.

- Come to a shared agreement.

- Clarify, challenge, summarize, and build on each other's ideas.

- Invite someone to contribute by asking a question.

- Show proof of listening.

"If you don’t show proof of listening, that means the person who’s talking doesn’t feel like they have the proper respect, and they don’t feel like they’re important in the discussion," explains Milo.

Guide Your Students to Reach a Shared Agreement

It's common for young children to stay stuck in their beliefs and want to get their opinions across, which is one reason why it's important for them "to try to reach a shared agreement," explains Gaunt, "but sometimes that's not going to happen." A shared agreement lets students know that it's OK to change their mind, as well as the progression of their discussion and how it's going to end: They will share their ideas, listen to each other, possibly change their minds, and then come to an agreement. Understanding the flow of discussion helps to guide them through it.

Help Your Students Analyze Discussion Guidelines

Use talk detectives -- one or two students who go around the room and observe their peers talking in group discussions -- not only to help enforce the guidelines but also to give students an opportunity to reflect on them. Your talk detectives will have a sheet of paper with the discussion guidelines on one side, and then three boxes to the right of it where they can write students' names and what they said that fit within the guidelines. "For example," explains Milo, "somebody might say they invited somebody to contribute by saying, 'So, what's your idea?' They would write their name and what they said."

"It’s getting the children to think about their conversations meta-cognitively," says Gaunt. "That’s been really successful."

Consider How to Group Your Students

Each grouping will yield a different type of conversation. Consider how to group your students based on the different types of conversations you want them to have. When starting out, focus first on teaching your students how to work in pairs. In the primary grades, School 21 largely uses pairs, trios, and traverse (see image below), and focuses on the other group structures -- like onion grouping -- as they get older. Each group configuration below shows different ways to do partner talk. "The colors represent partners A and B," explains Gaunt. "A blue dot is always next to a yellow dot."

"We do a lot of, 'Turn and talk to your partner about this,' but what we noticed was that children weren't actually listening to what their partners had to say," recalls Gaunt. "We had to teach them what good partner talk looked like," emphasizing:

- Looking their partner in the eyes

- Thinking about the volume they're speaking at

- Giving their partner personal space

Working in trios is good when students discuss talking points (usually controversial statements) where they start out by agreeing or disagreeing with the statement, and then work toward coming to a shared agreement among the group.

When they begin exploring how to talk in larger groups -- five or six members -- they start to take on roles to help them guide the discussion.

Create Discussion Roles

As adults, there are roles that we innately play in conversations, and we need to teach them to our students, says Gaunt, adding, "I used to think that if you let children talk, they'll just naturally be able to talk, but actually, we need to teach them how to talk."

In primary, there are three roles that School 21 focuses on initially: clarifier, challenger, and summarizer. "We need to teach them what those roles are, what they mean, what they look like in conversations, and the language and phrases that we might use if we're playing those roles" explains Gaunt.

To introduce conversation roles to your students, model them. School 21 teachers play recorded videos of themselves having conversations, and have their students analyze, identify, and discuss the roles they played. "They can then apply that to themselves and reflect back on what they're doing," says Gaunt.

Once your students initiate the roles without guidance, you can introduce them to other roles, like builder, instigator, and prober.

Create Structured Talk Tasks

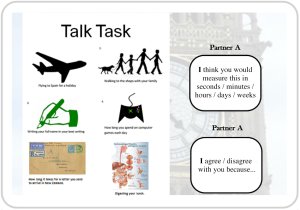

School 21 uses Talk Tasks, structured activities to help students discuss their learning within a lesson. They often use visuals to describe their Talk Tasks.

In a math lesson about how time is measured, they have a visual split into two columns. One column shows six images relating to different measurements of time, and the other one has sentence stems for partners A and B to discuss those time measurements.

Talking Points, a controversial statement to initiate discussion, can be used in any subject. Talking points encourage discussion by navigating away from yes or no responses to questions, introducing students to a format on how to carry out the conversation. Students will either start speaking by saying, "I agree with that statement because" or "I disagree with that statement because."

In School 21's history lesson on Ancient Greece, teachers used the talking point, "Beliefs were not important at all in Ancient Greece," and had their students talk in trios.

Ghost Reading is a cross-curricular tool for encouraging students to speak. Have your students read aloud a text together. Leave it up to them to determine how long they read and who reads next.

Collective Writing is a piece of writing created collaboratively. Pick a topic -- whether in science, English, history, or anything else -- and have your students take turns speaking about it. They can offer a paragraph, a sentence, or even a word, whatever they're comfortable with. Write down what your students say, and then read it aloud when they're done.

In studying Ancient Greece, teachers form groups of five and have their students reach a consensus on who should be the new patron goddess or god of the fictional city-state Dasteinia. They share background information with their students on the geography, leadership, and income of Dasteinia, and through the roles of summarizer, challenger, and clarifier, they discuss which god or goddess would be the best fit. One student acts as a spokesperson to share out their decision to the whole class, and another group member takes on the role of talk detective throughout the discussion.

Build Comfort and Confidence in Your Shy Students

With time, the foundations of oracy skills -- discussion guidelines, discussion roles, and choosing the level of participation in structured talk tasks -- build up a student's confidence around speaking.

To ease your students into talking, start them off with sentence stems -- a few words to help them start their sentence. This reduces the uncertainty of what they should say, gives them a framework on how to focus their sentence, and helps them to speak in full sentences.

"Sentence stems are a way of scaffolding people to talk, especially when people are less confident," says Gaunt. "If you give them that structure to hang their ideas and thoughts on, and they don't need to think so much about how they're going to start their sentence, they're more confident to just speak."

You can encourage your students to build on each other's ideas by using sentence stems. They can say, "Linking to So-and-So's point, I think that…" You can also use sentence stems to have your students explain their learning by saying, for example, "I started looking at this math problem by…" Below are more sentence stems that you can use in English, history, art, and science.

English

- A similarity between these texts is…

- A difference between these texts is…

- The author's choice of X shows…

History

- In this era…

- This artifact shows that…

- This source illustrates that…

- This source is biased because…

- This source is more reliable because…

Art

- I like this picture because…

- I prefer the work of X because…

- The composition of this piece shows that…

- The techniques I have noticed are…

Science

- The results show that…

- The conclusion I have drawn is…

- There is a correlation between ... and ....

- An anomaly I noticed is…

- I have observed...

Oracy is embedded in School 21's culture. Starting in primary, students build their oracy techniques in the classroom, every day and in every lesson. In secondary, they continue to develop their oracy skills through public speaking. "We're practicing it all the time in every lesson we're in," says Matilda, a Year 9 student, "and by the time you get to Year 9, it's almost instinctive."