‘I Wonder’ Questions: Harnessing the Power of Inquiry

Teachers can view students’ questions holistically and use them to develop lessons and projects that will harness student curiosity.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Students always have questions. When’s the homework due? How does Siri understand what I’m saying? Why is the sky blue? Student questions can be funny, insightful, and at times wildly off-topic. Rather than fielding these questions one-by-one when they come up, the teachers at Crellin Elementary record student “I wonder” questions so that they can view them holistically, and use what they find to develop lessons and projects that will harness student curiosity.

What Are ‘I Wonder’s?

“I wonder” is the categorical name that teachers at Crellin Elementary use to describe the individual questions that students ask about their learning. The teachers encourage their students to wonder out loud in the middle of a lesson.

Dana McCauley, Crellin Elementary principal, describes how the process works: “It’s when you are immersed in a lesson, and the kids are beginning to make those connections, and they start saying them out loud: ‘How are magnets related to electricity? Why is that in this unit? That doesn’t make sense to me.’ Or ‘Why is it that whenever we go to the stream, I’m seeing that green algae-looking stuff on there, when I thought you said we cleaned it up?’ Or ‘I’m wondering why is it that the salt melts the ice out there? Like why do we put that out there?’”

“I wonder” questions are whatever the kids are wondering about—whatever connections are happening in their heads as they learn, they’re saying these thoughts out loud.

Encouraging and Harvesting Student Wonders

Teachers at Crellin have different methods for recording students’ “I wonder” questions. Some have them write their questions before assignments during writing prompts, some simply write the questions on the board, and others may use posters or sticky notes.

“Some of them are irrelevant to what we’re doing at the moment,” says McCauley, “and you say, ‘Write that down; we’ll get to it later. Put it on a Post-it note.’”

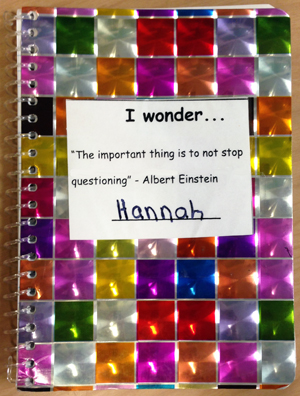

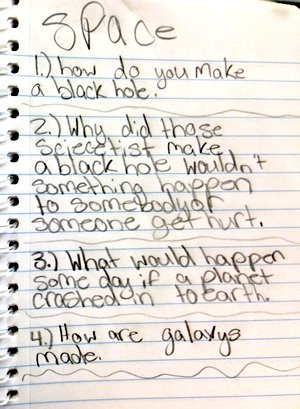

TIP: Have students capture their questions in “I wonder” journals, and use these questions to plan future lessons.

Fifth-grade students began using notebooks called “I wonder” journals after a regular learning partner, Dr. Dave Miller, realized that the students had far more questions than he could answer during his limited time in the classroom. He provided each student with a notebook and asked them all to write down everything they ever wonder about. Now he uses the journals to plan experiments for the students during his time in the classroom.

Regardless of the collection method, students are always encouraged to question, wonder, and share their wonderings with their teacher and classmates.

Channeling the Wonder

Every few weeks, teachers go through all the wonderings that have been collected but never addressed because they were off-topic during the lesson or more appropriate for a later unit. Looking at student questions as a whole, teachers can divine information about where the kids want to go, as well as where they have just been.

“They can be a clue to the teacher in making sure that no misconceptions are being created,” says McCauley. “You need to make sure that it’s flowing and that it’s making sense to them.... Is there a misconception in their understanding? Or is it sometimes that they are making a connection at a different level that you never even thought of? So it’s a way for us to reflect... about how we’re laying out lessons."

Teachers can also use “I wonder” questions to see themes and subject areas about which students are really curious, such as when fifth-grade teacher Brittany German noticed that she was getting a lot of “I wonder” questions about outer space. She then decided to use space in part of her next unit.

As teachers go through the “I wonder” questions, they ask themselves questions like:

- Where could I go with this?

- How can I tie some of these together?

- How can I make this meaningful for my students?

- What can I teach from this?

And while “I wonder” questions can definitely affect lesson plans, sometimes teachers use them in smaller, more individualized ways.

“Sometimes they’re not full-blown lesson plans,” says McCauley. “Sometimes it’s a project for one child to look at. Sometimes it’s more of a question that they need to research. Other times it turns into being a whole new project for the class or a group of kids.”

Leaving Some Questions Unanswered

Students can have dozens and dozens of questions, and the thought of answering all of them could be overwhelming to some. But Crellin teachers say that they don’t feel obligated to answer every question asked. They aim to fold in what they can, encourage students to take ownership and seek answers on their own, and most of all, encourage students to continue asking questions. Principal McCauley believes that continued wondering is the ultimate goal: “If they don’t wonder, ‘How would we ever survive on the moon?’ then that’s never going to be explored. You want to encourage it enough that they continue to ask with the understanding that not all will be answered. But that doesn’t mean they should stop wondering, because wonderings lead to thinking outside the box, which makes them critical thinkers. As they try to figure it out, and reflect on what they’re doing, that’s where it all ties together for them. That’s where all that learning occurs—where all the connections start being made.”

Resources:

- Rubric for Discipline-Based and Inter-Disciplinary Inquiry Studies (Galileo Educational Network)

- Excerpt: "Teaching for Meaningful Learning: A Review of Research on Inquiry-Based and Cooperative Learning" (Teaching for Meaningful Learning)

- 4 Phases of Inquiry-Based Learning: A Guide for Teachers (Teach Thought)

- Teaching History by Encouraging Curiosity (Edweek)

- The Case for Curiosity (Curiosity Now)

- Fostering Curiosity in Your Students (Education Oasis)

- Plant Growth Experiments (Crellin Elementary)