Helping Students With Identity Secrets

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Hidden Selves

Jake's hands were clenched and he had a weak smile on his face when he told me the joke his friends were laughing about. "I laughed, too," he said, "but inside I was filled with fear, fear that they might find out." Jake, a tall, slender high school junior, was referring to a gay joke that while not malicious, was a degrading word play. Jake is not alone.

Sarah was a fifth grade Muslim girl whose family is from the country of Georgia. Her parents were afraid that she would be insulted and shunned if it became known what her religion was, due to strong negative feelings about Muslims in her community. They said, "Just the way some people talk about President Obama being called a Muslim, as if it was a terrible thing, scares us." They changed her name to Sarah and forbade her to wear a hijab in school, even though she was very proud of her heritage. Like Jake, she was afraid that others might find out. One obvious solution for her was a private Muslim school, but there were none close enough for her to attend.

Billy was a very light-skinned African American who tried to pretend he was white. The wonderful Denzel Washington movie, Devil in a Blue Dress, uses a black woman "getting over" as white person as its central theme. While no longer a common goal for black folk, it still happens often enough to raise issues for some students.

In these three true examples, the students also felt afraid that their parents would find out as well as their classmates. Jake was afraid to tell his parents that he was gay. Sarah and Billy didn’t want to embarrass their parents by letting their secrets out.

Other identity secrets include certain forms of physical disabilities or perceived ugly birthmarks.

Most, if not all, children have secrets, including family members at home with drug and alcohol problems, poverty, abuse or even something as simple as having a secret crush for another student. But these secrets are different. Identity secrets reflect a fear of discovery about who they are, not the circumstances they are in.

No one can learn when living with a daily fear of being "found out, not only by other students, but by teachers." Can schools do anything to help students with secrets like these?

3 Steps Toward a Culture of Acceptance

Because we are professionals, the nature of these identity secrets is totally irrelevant to us, regardless of our feelings about sexual orientation, religion or race. We must ensure an emotionally safe environment for all students regardless of who they are. Of course, we must intervene when a student's secret is an illegal act like selling drugs or attacking other students online, but those secrets are not based on identity.

It is a cliché to say that all schools should encourage a culture of acceptance and safety, because all schools already promote this attitude, although some are better at it than others. But this issue is far more complicated. Whether or not a student chooses to reveal his or her identity secret is beyond the scope of the school. The consequences of "coming out" are severe for these students, well beyond the walls of school. Our goal is not to help them reveal, but to feel safe in keeping their secrets, unless they decide it is in their best interest to tell others. Here are three suggestions that can help.

1. Remain Confidential and Professional

If a student with such a secret decides to trust an adult in the school and reveal it, the adult has the responsibility to keep the information private for as long as the student requests it. The adult also has the responsibility to be a safe harbor for that student and to communicate respect and acceptance. At the same time, all professionals must inform students that if they reveal any illegal activity, they are obligated to tell the police, and if students reveal any abuse, even self-abuse, that they must report it to social services.

2. Teach Trust and Self-Knowledge

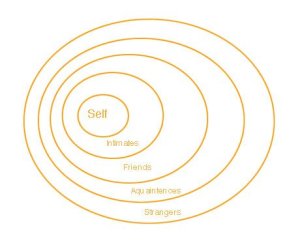

The school can teach all students not to feel guilty for having a secret, that all people have information that they have a right to keep private. Dr. Sidney B. Simon taught a strategy of extended circles starting with self, followed by intimates, friends, acquaintances and strangers. His students then decided what kinds of information about themselves belonged in each circle. Using strategies like this can help students reduce the guilt of withholding their secrets from others.

We can teach students that it is usually better to move information in the self category to the intimate category, because secrets are a burden and sharing them can be a way of getting help. Problems like eating disorders or online addiction, for example, can be helped when shared with the right person. We can also teach students that the best time to share is when they are ready and have someone they trust. Additionally, they need to learn both the positive and negative consequences of sharing. The most important point of this lesson is that everyone has limits on what and with whom they can share. It is healthy to understand the nature of secrets and how to make the best decisions concerning them.

3. Teach Respect and Inclusion

Adjust the school policy and culture to remove or severely reduce jokes, slander, insults, hurtful comments and other destructive expressions about others. It should be included in the rules, but that is not enough. Use student groups to post announcements of this policy and belief system online and on walls throughout the school. Practice with students how to say, "That comment has no place in this school." Each class can have a rotating leader whose job it is to monitor hurtful comments about "the other." English and history classes can focus some stories about how society treats "the other," and the consequences of doing so.

Great teachers, counselors and schools support and protect students that fit in and fit out equally, because school is for all students at all times.

Have you experienced these issues in your school? How have you approached them?