Creating Space for Tasks That Are Important but Not Urgent

A priority-setting tool used by President Eisenhower can help school and district leaders ensure that they’re focused on the right tasks.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.At the risk of stating the obvious, time is a school administrator’s most precious and consequential asset. But time is unique, too: Unlike other resources, once spent, it can never be recovered. As a school leader, how you spend your time will in large part determine the professional and organizational objectives you’re able to accomplish, the kind of leader you’re perceived to be by the school community, and whether you’re able to achieve a healthy balance between your work and home lives.

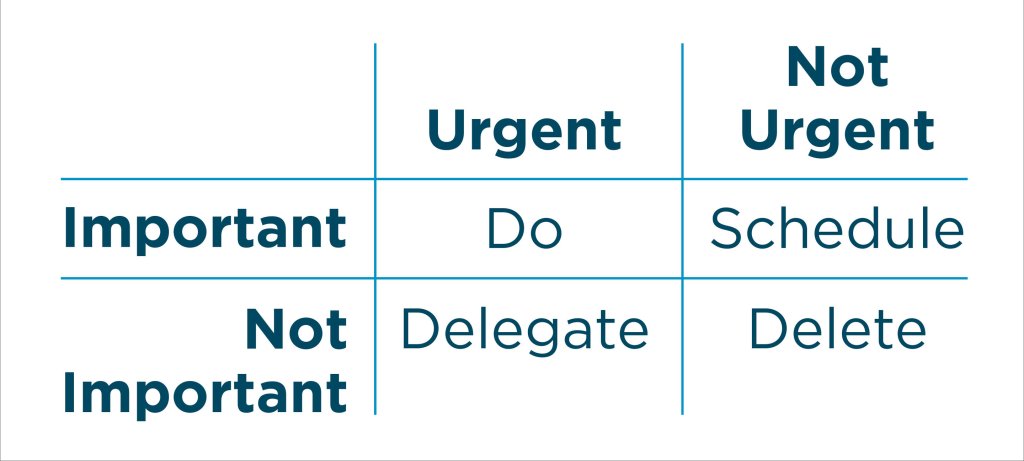

The Eisenhower Matrix

Undertaking the formidable duty of leading Allied forces in World War II, Dwight Eisenhower created the classic time management schema known today as the Eisenhower Matrix.

Administrative tasks, according to this matrix, can be classified simultaneously as either important or unimportant, and as urgent or nonurgent.

Urgent and important tasks: These are tasks that must be handled immediately—for example, a safety crisis. But if a school leader’s day consistently careens from one crisis to the next, it is a certain indication that systems designed to manage routine tasks and prevent crises are inadequate.

Urgent yet unimportant tasks: These include addressing minor disciplinary incidents. They may be delegated to assistants (e.g., administrative assistants or assistant principals) with supportive training provided.

Unimportant and nonurgent tasks: These, by definition, are avoidable. Effective time management is usually an exercise in subtraction.

Important but not urgent tasks: This is the zone in which effective leaders, Eisenhower asserted, devote 60–80 percent of their time. These are strategic planning initiatives likely to produce long-range mission-critical results. Perhaps the best school-based example, validated by voluminous research, is instructional leadership: regularly conducting learning walks, planning professional development, and reviewing data regarding student achievement.

Prioritizing important, nonurgent tasks

To develop a baseline that identifies your current time allocations, sketch your own Eisenhower Matrix and estimate the percentage of time you spent in each cell. Repeat the exercise every Friday for a month. What patterns emerge? What steps did you take during the month to maximize important yet nonurgent tasks, while minimizing the other three categories? Once you sketch out your own time allocations, some of these points can help you allocate your time more effectively.

Your calendar dictates your day: Because important, nonurgent activities are not time-sensitive, many administrators do not bother to mark them on their calendars. Then time tends to slip away as you answer one more email or phone call, until you find yourself saying, “I never got to the learning walks.” We learned to ”calendarize” these activities—jot them on the daily calendar—and treat them like any other scheduled event. This meant no cancellations except for emergencies. Administrative assistants were asked not to interrupt during this time; even when the superintendent or board president called, our staff informed them that they’d get a call back in an hour or two.

Another way to solve the “tempus fugit” problem (Latin for “time flies,” the maxim dating back to Virgil) is to set a numerical goal: For example, resolve to spend an hour a day in classrooms or visit two grade-level team meetings per week... and mark them as regular appointments on your calendar.

Touch it once: The antidote to the endless torrent of email calling for an administrator’s attention may be found in another classic time management principle: “Touch it once.” Some email requires extensive follow-up, but most can be addressed once and then put to bed. Deferring a response only compounds time management problems as your inbox continues to expand. We suggest reserving a set time period, say 30–45 minutes after school, to the Sisyphean task.

Think time: Busy administrators live in the moment, discharging immediate objectives with scant time to study a problem in depth, partake in long-range planning, or detach from the here and now long enough to think outside the box. To remedy this problem, we recommend setting aside “think time” on your office calendar, a two- or three-hour sacrosanct block of time that you reserve for taking a deep dive. In this time, you can research a critical issue facing the school, call expert colleagues to pick their brains, examine data or samples of student work, or convene a focus group.

A little ‘me time’: To reduce stress and maintain a positive outlook, set aside daily personal mental health breaks. Even a marathon runner—an apt metaphor for a school leader—grabs water for nourishment now and then. While it would be wonderful to identify best practice in this regard, how one makes time for this self-care really depends on the demands of one’s own setting. Some leaders integrate meditation or breathing exercises into their daily routines. Some carve out time for a coffee break. Since lunchtime is an optimal time for staff and students to drop by, don’t expect an uninterrupted lunch. Instead, try this rule (admittedly a low bar): “No eating standing up.”

You are what you do: The impact of time management extends well beyond task efficiency. Members of the school community recognize a leader’s priorities by what they observe the leader doing. Setting aside time immediately before and after school to implement an open-door policy demonstrates that you’re approachable and you value conversations with staff and teachers. Devote substantial time conferring with student groups, running the school talent show, joining students for lunch or recess, and you’re delivering a powerful message about the primacy of relationships with students.

If you are a district leader, there is similar value in scheduling time to be visible in the schools, where you can meet with school building leaders on their own turf, as well as engage with teachers and other staff, and, when practicable, students.

Every day do something that makes a difference: School leadership is an incredibly rewarding profession, yet there will inevitably be days devoted to legal hearings, writing mandatory reports, attending to bus delays, and the like. Try to reserve time every day to advance a goal you care about deeply: In addition to serving institutional goals, this time management strategy is a morale booster. Counteract the necessary bureaucratic element of the job with a task that is meaningful and makes a difference in the lives of students and the health of the school community.