A Look at Implicit Bias and Microaggressions

A primer on the impact of implicit biases in schools and how they can be expressed by students and faculty.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Like everybody else, I possess unconscious biases about people that are contingent on how they talk and look. Such instant judgments, called implicit bias, involve “automatically categorizing people according to cultural stereotypes,” Sandra Graham and Brian Lowery write in “Priming Unconscious Racial Stereotypes About Adolescent Offenders.”

The consequences of implicit bias in schools are both powerful and measurable. A 2017 study by Hua-Yu Sebastian Cherng, for example, found that “math teachers perceive their classes to be too difficult for Latino and black students, and English teachers perceive their classes to be too difficult for all non-white students.” In English, these biases lower the affected students’ “expected years of schooling by almost a third of a year.... The effect of being underestimated by math teachers is −0.20 GPA points.”

Implicit bias also leads to inequitable punishments for students of color. A 2012 investigation found that “17 percent, or one out of every six black schoolchildren enrolled in K–12, were suspended at least once,” compared with “one in 20 (5 percent) for whites.” Black girls ages 5 to 14 have been viewed by adults as “less innocent” than white girls of the same age, which may be a factor in the disparity in suspension rates, according to a 2017 report by Georgetown Law’s Center on Poverty and Inequality.

Implicit Bias and Microaggressions

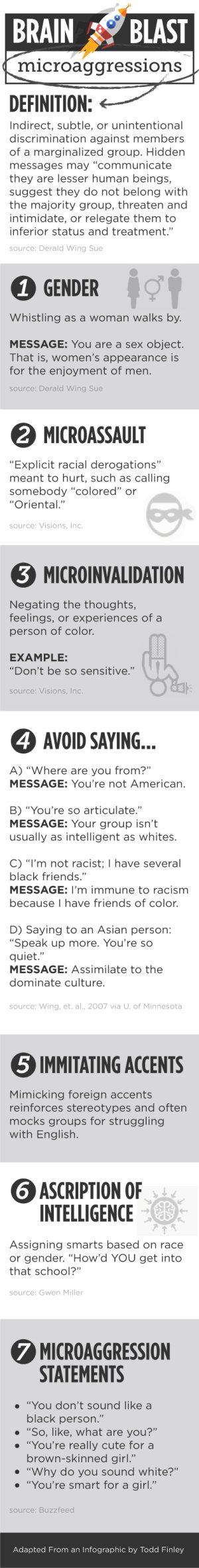

Microaggressions are one outgrowth of implicit bias. Columbia University’s Derald Wing Sue defines this term as “prejudices that leak out in many interpersonal situations and decision points”; they are experienced as “slights, insults, indignities, and denigrating messages.”

In a 2007 article for American Psychologist, Sue and six other researchers identified three categories of racial microaggressions:

- A microassault is a “verbal or nonverbal attack meant to hurt the intended victim through name-calling, avoidant behavior, or purposeful discriminatory actions.” Example: Students wear Confederate flag clothing.

- A microinsult is insensitive communication that demeans someone’s racial identity, signaling to people of color that “their contributions are unimportant.” Example: A teacher corrects the grammar only of Hispanic children.

- A microinvalidation involves negating or ignoring the “psychological thoughts, feelings, or experiential reality of a person of color.” Example: An Asian American student from the U.S. is asked where she was born, which conveys the message that she is not really an American.

Over the years, the concept has been extended beyond race to include similar events and experiences of other marginalized groups, including women, LGBTQ people, people with disabilities, etc.

In schools, students report that experiences like these are fairly common:

- “In high school, boys in my math classes would look over my shoulder and unsolicited point out my errors with their pencils.”

- “Sometimes I’m asked, ‘Why are you so white?’ meaning that people with Arab names and heritage are supposed to be all dark-skinned, and I’m asked to justify my skin color and explain why I don’t match their racial stereotypes.”

- “I’ve been told, ‘Go back to Mexico!’ many times.”

Other microaggressions include teachers being surprised by certain students’ achievements or holding tests on religious holidays, and peers imitating foreign accents or saying, “That’s so gay,” or “She’s so bipolar.”

Starting Important Conversations, and Keeping Them Going

Once during a faculty meeting, I witnessed an educator tell a white male colleague that he’d committed a microaggression. At the time, I didn’t know precisely what that meant. Nobody talked for a few uncomfortable seconds until someone changed the topic. Calling the man out in the moment was justified. After all, it’s everybody’s job to make diversity-sensitive norms explicit. But that moment was also a dialogue killer. Had there been previous conversations among the entire faculty about microaggressions, perhaps the entire incident could have been avoided.

Thoughtful conversations are also halted by whataboutism (“Why do they get to use racist words and we don’t?”), name-calling (“snowflakes,” “thought police”), and the unfortunate formula “strategic denial plus conjunction plus racist comment” (“I’m not racist, but...”).

How do you have a meaningful classroom dialogue about microaggressions? The trick is to plan a conversation on this topic before microaggressions ignite tensions. Set discussion ground rules, like “commit to learning, not debating,” and then show examples of microaggressions as a prelude to discussing why they’re hurtful.

If these types of conversations feel too challenging to you, contact a nearby university’s office of diversity and inclusion and invite someone with expertise in sensitive topics to address the class. They’ll model how to handle this discussion, so you can take the lead next time.

Resources to Counteract Implicit Bias and Microaggressions

There are a number of resources that can help K–12 faculty and adolescent learners counteract implicit bias and avoid the perpetuation of microaggressions.

Videos: Watch and discuss Dr. Yolanda Flores Niemann’s “Microaggressions in the Classroom” and Ahsante the Artist’s “I, Too, Am Harvard” during the next faculty meeting.

Checklists: Read “Microaggressions in the Classroom,” developed by the University of Denver, as well as Kevin Nadal’s list of microaggressions that harm LGBTQ people.

Activities: Sign up for a seven-day bias cleanse that emails daily tasks to reorient your thoughts on race, gender, and anti-LGBTQIA bias. And try Harvard’s Implicit Bias Test.

Readings: Check out multicultural texts suggested by the American Library Association.

Norms: Learn about culturally inclusive classrooms and establish classroom ground rules that promote inclusive language and behaviors.

Students and teachers are made of powerful feelings, but these feelings are not fixed and set in stone. Emotions can be identified, excavated, understood, and managed. And when we work through that process together, implicit bias can be unlearned.