9 Dynamic, Hands-On Activities That Immerse Students in Civics

Civics takes on new life when students have real-world experiences like creating polls or ballots or touring a local government building.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.The founding fathers knew drafting and signing the Declaration of Independence would be viewed as a flagrant act of rebellion against the British Crown.

Treason, punishable by death—yet they did it anyway, for the greater good, for freedom. If tasked with an age-appropriate moral and ethical dilemma, would your students do the same?

High school history teacher Nicholas Ferroni knows the answer to that question. “Think of five things that benefit the majority of students to make things better for you guys,” he said to his class. “School policies, page 32, section 7b of the school handbook states: ‘In order to establish a fair and balanced school climate, students may suggest and even petition for new school policies with 10 percent of the size of an actual class.’”

Kids got to work brainstorming topics to advocate for and wrote a petition to amend the school’s dress code to be more equitable, add career-based and life skills classes, and set a later school start time. Students got up one by one to sign the petition, and Ferroni delivered it to the principal.

Seemed easy enough, until Principal Lowery barged in mid-class—à la King George. “You sign that petition, you won’t graduate here, you will not walk, and you will not go to prom,” he threatened. Students were confused, Ferroni appeared to be as well and offered students an opportunity to remove their signature. A few stood up, tempted and nervous. Their classmates tried to talk them out of it, and chaos ensued, but then Ferroni revealed that it was all a ruse—designed to give the students some sense of what the founders went through.

Activities like this can bring civics to life, illustrating the importance of civic engagement and helping students identify their core values—as well as “how much they’re willing to sacrifice for what they believe in,” Ferroni says. Being able to lobby support for a bill or to visit a courthouse and meet with a judge, for example, and really “seeing how the government works firsthand” is more impactful than “just listening to lectures,” says AP government and civics teacher Jennifer Klein. Her students agree, noting that her class is full of “fun, exciting group activities that allow us to engage socially while efficiently learning.”

Whether it be through internships or opportunities to speak with representatives, do community service, or propose new school policies, real-world civics activities make what students learn in social studies “much more tangible and meaningful,” echoes Spencer Burrows, a secondary school equity and civic engagement coordinator. “I’m hoping it leaves more of an indelible mark on the students and gives them the motivation to pursue these things,” he told Edutopia. “Give them a couple options, and they’ll find something that speaks to them, something they want to get involved in.”

9 Real-World Civics Experiences

1. Poll the Public: To better understand how the public views certain political issues or topics, you can have students create and disseminate a survey. They can poll their classmates or the wider student body, or even expand beyond the school walls.

Burrows likes to keep in close contact with local lawmakers’ staff members, picking their brains on what projects they have going on or could use some help from students with. When State Senator Ben Allen was chair of the Senate Education Committee for California, Burrows says, his office was very willing to work with schools.

“He would send us on missions like, ‘Can you go and poll on measure ABC?’” Burrows says, adding that these are things he wouldn’t have thought to do on his own. “Middle schoolers had a great time jamming people up on the street corner. The lawmakers enjoy getting to involve the local youth, and it gives our kids something real to do.”

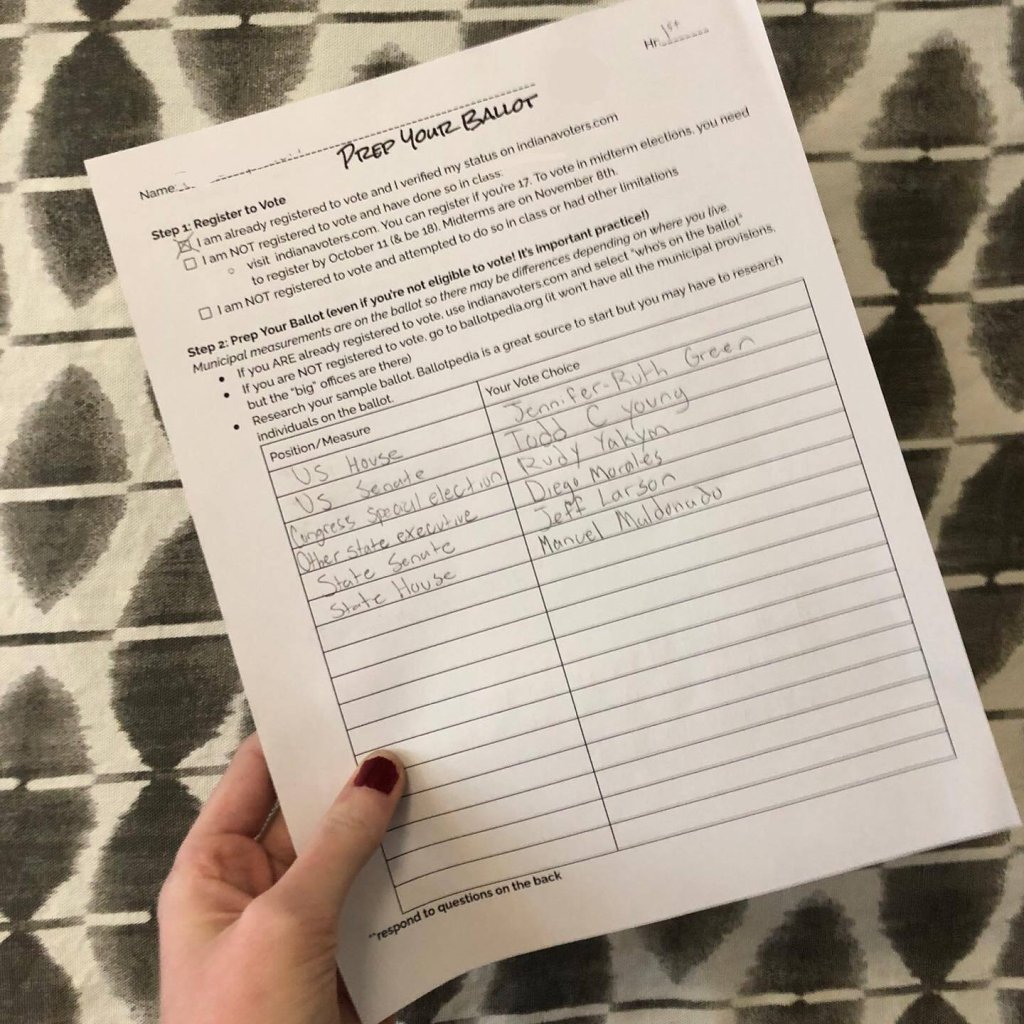

2. Prepare a Sample Ballot: To help familiarize students with the voting process before participating in a real election, high school government teacher Kendra Parker has them research and prepare a sample ballot. After walking the class through their state’s online voter registration process, students use the voter portal to identify which candidates and issues will appear on their ballot. In lieu of an active election, you can use a sample county ballot from a previous election.

“I model for them how I find information and explain some of my thought process for positions,” Parker told Edutopia, recommending to students resources such as Ballotpedia, Vote411, and their local library’s online civic engagement offerings. Students next record their selections on a handout and complete reflection questions evaluating “how simple or complex they thought the system was and identifying their key factors in determining how to vote.” The handout doubles as a tool they can bring with them to the polls.

3. Create Space for Civil Conversations: Democracy is a “system built upon civil discourse as the means to work out our differences peacefully,” educational consultant Tom Driscoll and former educator Shawn McCusker write, but this sort of conversation seems increasingly hard to come by. “According to Pew Research, 45 percent of Americans report that they have stopped talking to someone as a result of their political views,” the pair write.

To revive the spirit of civil discourse and help your students develop the skills they need to engage in it, high school teacher Peter Paccone suggests having students plan what he calls a Lunchtime Open Forum. This event is an opportunity for “students, teachers, admins, staff, and at least a few (by-invitation-only) members of the general public to come together once a month to civilly discuss an issue of contemporary significance.” Paccone suggests checking out KQED’s Above the Noise videos or the ProCon website for potential issues to discuss—such as if voting in the United States is too difficult or if the legal voting age should be lowered to 16.

4. Stop the Spread of Fake News: False information is all over the internet—that’s nothing new—but “now that anyone with access to a phone or computer can publish information online, it’s getting harder to tell,” writes former editorial director of Common Sense Sierra Filucci.

Students can play a role in helping their family and friends think a bit more critically before believing everything they read online by creating a media literacy guide. After compiling resources from trusted sources—the College Board suggests using Newseum, Media Literacy Now, or PBS NewsHour—on how to best approach new media outlets, kids can lay everything out using design tools like Canva, record short videos using Flip, or create PowerPoint presentations.

5. Tour a Local Government Building: An in-person tour at a government building allows students to see how systems they’ve learned about actually work in practice. Burrows likes to first understand “where students came from” and what they know, and then focus on “how you can build on that and extend it.”

For example, eighth-grade students had learned about the criminal justice system, so a field trip to the courthouse to meet a judge was particularly resonant. Students were “super interested,” Burrows says. “A judge came and told them all about some of the crazy cases he’s done. They were supportive of it being a real courtroom, the real judge, and hearing the stories and tying that back to the stuff they’ve done in the classroom.”

6. Exercise Your Rights: After completing a project about First Amendment rights and an in-depth examination of the origins of the Constitution, educator Stacy Saltz provides students with a choice of how they’d like to exercise their rights. Here are some options:

- Attending a march or rally

- Attending a religious service they have never attended before

- Creating and administering petitions for change at school or in their community (homeowners association, city, etc.)

- Writing a letter to a government official asking for change

- Writing a letter to the editor of a news publication

- Speaking at a school board; parent, teacher, student association; or city council meeting

Afterward, students reflect in writing about how this connects to their lives and what they’ve learned about the Constitution. “It allows them to see themselves as change makers,” Saltz told Edutopia.

High school civics teacher Hal Biehl does something similar, requiring students to attend at least one municipal or school board meeting. They collect their observations in a report that they present to the class.

7. Each One Teach One: “One of the best demonstrations of mastery of a specific skill is to teach that skill to someone else,” writes high school English teacher Jason Abril. Students are often very proficient teachers, something Burrows uses to his advantage.

He assigns students from each grade a different topic—local, county, state, and federal government, for example. “Students create a canned lesson about that, which they then present to each grade level,” he says. This is a great way to encourage students to engage in civics-related conversations that sharpen key skills like research, oral presentation, and reflection.

8. Inform the Public: The College Board suggests having students create a citizen action campaign—creating a blog, flyer, or video public service announcement using YouTube or Flip “to inform or persuade others.” Topics can range from environmental conservation to gun violence prevention—anything that motivates your students to take action. They can take things one step further and pound the pavement, spreading the message around the school, at the local library, or at other places where people congregate.

As students “become experts on a topic and discover why something is an issue,” you will see their enthusiasm and curiosity bloom, writes fifth-grade teacher Jessica Cambell.

9. Become a Global Citizen: Many students might learn about our own government and stop there, but Burrows likes to encourage his students to expand their horizons. Learning about the governments of other countries provides interesting cultural perspectives, helping students develop a broader understanding of political dynamics globally.

Burrows set up a joint project where his students and students from another country could teach each other about their respective governments. The U.S. Embassy introduced him to a Croatian high school teacher who ended up being a perfect fit. “It doesn’t hurt to ask,” he says of contacting the embassy. “Send out your request and someone’s going to get back to you, or somebody knows somebody who knows somebody who might be interested.”

Because of the time difference, finding a slot for the two classes to talk in real time wasn’t possible, but students recorded and replied to each other’s videos using Flip. “As we were going back and forth educating each other, our kids are watching these videos like, ‘Oh my God, these Croatian kids know a lot about American politics. We don’t know anything about Croatia,’” he said. “The entire world does not revolve around America. As much as we think we’re important, and we obviously have influence in a lot of ways, everyone’s got their own issues, their own problems, and things they’re trying to work through.”