How to Move From the ‘Main Idea’ to ‘Background Knowledge’

Traditional approaches to reading instruction—such as finding the ‘main idea’—are less effective than a knowledge-rich approach, the research shows.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.“In a fit of anger, Moses smashed the tablet against the ground.”

A group of young students reading that sentence will come to different conclusions. Depending on how familiar they are with the Bible, some may recognize it as a parable. Others may reel at the thought of an expensive electronic device being destroyed in a fit of pique. For linguistics and literacy researchers Carsten Elbro and Ida Buch-Iversen, coauthors of a landmark 2013 study on background knowledge, the difference between the two interpretations has little to do with a student’s reading comprehension skills.

Students who properly decode the words and understand the basic structure of a text may still come up short in measures of comprehension because they fail “to activate relevant, existing background knowledge,” Elbro and Buch-Iversen explain in the study. That’s because students constantly make inferences and seek connections to their lives to make sense of what they’re reading—understanding what Moses was actually doing depends more on whether you were raised as a Christian than on your ability to grasp the sentence’s literal meaning.

In their study, Elbro and Buch-Iversen separated 236 sixth-grade students into two groups. One group of students used concept maps to connect related ideas—an exercise that helped them build a lattice of intertwined knowledge across subjects like biology, technology, sociology, and history. The second group participated in business-as-usual instruction centered around reading strategies such as summarizing and making predictions. After eight 30-minute sessions, the background knowledge students scored twice as high on tests of general reading comprehension, compared with their peers, with sizable improvements across fiction and nonfiction texts.

A decade later, new research—this time encompassing more than 10 times the number of students—confirms those findings. A groundbreaking Harvard study published last year investigated the benefits of a 10-week, knowledge-rich approach to building reading comprehension in elementary students. Instead of emphasizing traditional skills like identifying the main idea or citing evidence from the text, the researchers asked the youngsters to read widely on a topic in order to develop “generalized schemas that can be accessed and deployed when new, but related, topics are encountered.” Students read about dinosaurs, for example, and thus build a deeper understanding of how scientists collect data to study past events. Those students scored 18 percent higher on later, science-related reading comprehension tests, compared with their peers.

Here are six prereading activities to help students build background knowledge and fill in conceptual gaps before tackling new texts.

1. Sustained inquiry. “When I started looking into what’s called the achievement gap in education, I was told that the problem was high school,” Natalie Wexler, author of The Knowledge Gap, told Edutopia in 2022. “But the problems that become really obvious in high school, for the most part, have their roots in the way we teach elementary school.” In successful elementary schools, Wexler noticed that English language arts (ELA) lessons often looked like they belonged in science classrooms—in one example, fourth graders studied detailed anatomical diagrams in ELA and learned words like cardio and circulatory. By committing content knowledge to long-term memory, these students were able to continue exploring the topics while devoting more working memory to comprehension, Wexler discovered.

Wexler’s observations align with what experts recommend: a sustained, thoughtfully sequenced, content-oriented approach to building strong reading skills. When planning for the academic year, “consider the topics to be covered for the year and then ask yourself, ‘How can we integrate instruction around a coherent schema?’” suggest James Kim and Mary Burkhauser, who led the Harvard study on background knowledge. Instead of covering one topic and then moving on to something unrelated, look for ways to tie broader themes together, and revisit and reinforce them often: “Consider larger schema (the trees) that connect the topics (branches) you are expected to cover.”

If students are going to read about Roman emperors, for example, you can prepare them by exploring and reading widely across related, universal themes like civilization-building, governance, and codes of law, helping to build a rich foundation of vocabulary and thematic knowledge that students can access as they read future texts that touch upon the same concepts.

2. Vocabulary games. In a 2019 study, students who were familiar with less than 59 percent of core terms in a topic struggled to understand the reading material. But quickly memorizing new terms in isolation won’t result in lasting recall.

Consider spending more time on vocabulary acquisition, be multimodal, and make connections to other learning, writes Rebecca Alber, an instructor at UCLA’s Teacher Education Program. She recommends using photos to introduce new words to kids or connecting the words to things they’re familiar with, are interested in, or have learned before. Students can also draw the words or work in small groups to talk about them. The dictionaries shouldn’t come out until students have worked hard to discover the definitions on their own, Alber suggests. As the list of foundational vocabulary grows over the course of the year, try word sorts—grouping words with related meaning together—or pick five terms from the course and ask students to chat quickly about how they are interrelated before they each write a quick paragraph linking the terms.

Instructional coach Hannah Bradley builds engagement by playing word games—an approach that works across subjects and age groups. “In my experience, the lighthearted nature of these games provides students with a fun, safe, and low-stakes environment where they feel more confident to just have a go,” she writes. A great starter activity is From A to Z, a five-to-eight-minute game in which students work in small groups to brainstorm words related to a topic being studied for every letter of the alphabet. Word-association games like Just One or Telephone Pictionary can help students see how concepts are interrelated, building a more robust network of interrelated ideas.

3. Station rotation. Before jumping into a new lesson, you can set up several tables with related reading materials—comics, photo collections, poetry, introductory videos, or news articles, for example—to give students multiple entry points while building familiarity with key events and people, says high school social studies teacher Tim Smyth. When Smyth starts a unit on World War II, he sets up seven tables, each with a central theme—Holocaust, leading women, and key battles, for example—which students dig into while taking notes. They also answer reflection questions such as, “Describe one image you saw that jumped out at you. Why did you choose this one?” or “What are three questions you have/want to know more about?”

“As we delved more deeply into World War II content in the weeks following book study, students made powerful connections between new content and the texts they explored at the start of the unit,” writes Smyth. “And they were better able to retain the information and see the bigger picture by referring back to the texts they explored.”

For topics that students learn at a younger age, you can use materials they’re already familiar with—using clippings from National Geographic to explore different ecosystems, for example, or short YouTube videos that delve into an interesting topic like how cavities form or what germs are—to build engagement and introduce complex ideas. Graphic novels can be used to introduce challenging concepts, says middle and high school teacher Jason DeHart, while excerpts from your students’ favorite sci-fi or historical fiction novels can be entry points to reading more complex texts. By starting with materials that students are already familiar with, you’re helping students make connections to new ideas that may otherwise be elusive.

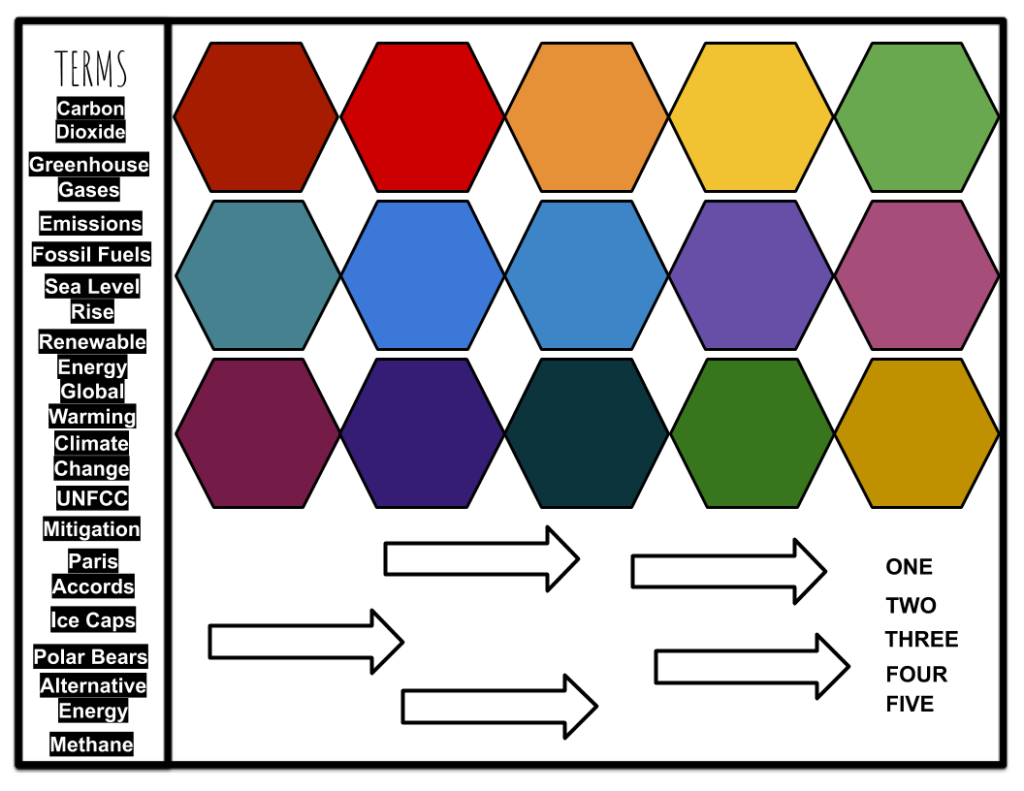

4. Hexagonal thinking. An engaging pre-lesson activity that doubles as a way to refresh what students have learned and help them make new connections, hexagonal thinking uses cut-out hexagons—each covering a single term or concept—to explore novel insights. Working in small groups, students first create or are given a list of key ideas, which are then written on separate hexagons made digitally or from paper, card stock, or sticky notes. Students then connect the hexagons, linking related ideas together. For example, if students are learning about animal habitats, they can arrange animals by biome (forest, plains, desert) and investigate similarities and differences. Each group may have a completely different configuration of hexagons, providing fodder for a creative discussion.

5. Tools to map the conceptual terrain. If you’ve ever jumped into a book (or television) series midway, you know that it can be disorienting. That’s because a good story relies on familiarity with past events to keep the audience from getting bogged down. Similarly, students with ample prior knowledge are more likely to keep pace with a lesson.

When starting a new lesson, students unfamiliar with the topic are often overwhelmed by the amount of new information they need to process. Using graphic organizers—anchor charts and concept maps, for example—can help them map the conceptual terrain, bringing into sharp focus the difference between main ideas and support details, or how big concepts relate to each other. In a 2021 study, middle school students who used graphic organizers to organize their thinking around the topic they were learning about—the seasons—improved their factual recall by 45 percent and comprehension by 64 percent, compared with students who had simply studied the material.

For fictional texts, K–8 special education teacher Dianne Stratford recommends using story maps—an activity that helps young readers “understand the elements of a story, such as characters, setting, problem, and solution, or sequential points of the story, such as beginning, middle, and end.” Not only will it help students remember the story, but it’ll help provide a framework for understanding any future texts they encounter.

6. Pretending to learn. In Oscar Carillo’s kindergarten class, students learn about the different parts of a car—the pedals and wheels, for example—while dashing around the room making “Vroom, vroom!” sounds. In another story, they pretend to be sharks and turtles swimming through water. Not only does it strengthen oral language skills, says Principal Sarah Bartels Marrero, but also it helps them “understand the shape of a story.”

Asking young learners to imagine story events and engage in pretend play as a prereading activity helps them build “world knowledge,” according to a 2018 study. When preschoolers spent 10 minutes pretending that they were chefs in a restaurant cooking pizza—rolling the dough, adding toppings, and then baking the pizza, for example—they predictably outperformed their peers (who had played with unrelated toys) on tests on pizza-making knowledge. The pretend-play kids were also able to make better inferences—reading between the lines to answer questions around a character’s goal or motivations, for example—outperforming their peers by more than double.