An Engaging Word Game Helps Students Grasp Implicit Bias

A simple fill-in-the-blank exercise helped students understand the power of words and the way they might convey unspoken beliefs.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.As part of an effort to demonstrate the effect of implicit bias, library media specialist Jacquelyn Whiting devised an exercise that looks similar to “Mad Libs,” the popular fill-in-the-blank word game. In EdSurge’s “Everyone Has Invisible Bias. This Lesson Shows Students How to Recognize It,” Whiting describes how she removed words from a New York Times opinion essay to create a new, highly engaging activity for a 10th-grade class.

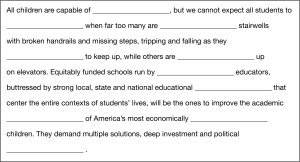

Whiting removed key words from the essay to create a paragraph for students to fill-in-the-blank. A student's goal “is to make the paragraph cogent, to choose words that make sense in context,” Whiting writes. “And second, they needed to do it alone, without discussion.” The students breezed through the first few blanks, but the exercise became more difficult as they progressed. After they completed the task as individuals, Whiting asked them to gather in pairs or groups of three. “This time they needed to discuss the task and agree on the words that filled each blank,” she writes. “Again, they cruised through the first few, easily agreeing about what the missing words could be. And then it got harder.”

Sharply conflicting viewpoints emerged, and it became more obvious to the students that word choice matters. In the phrase “they _____ to keep up, while others are _____ up on elevators,” students discussed the difference between filling in the first blank with “struggled,” “tried,” or “attempted.” The students grasped that all three words conveyed a lack of effort or agency and expressed surprise when the original writer’s actual words were revealed: “they work to keep up, while others are zooming up on elevators."

The discrepancies were revelations to the students “many of whom had been classmates for years, who lived in similar neighborhoods and took multiple classes together.” The importance of the use of language became apparent in a seemingly simple exercise, and they realized “that their choice of words indicated subtle and even unconscious beliefs,” Whiting writes. In addition to understanding their classmates differing points of view, they also gained an important insight: “things they thought were fact might actually be opinion.”

Whiting walked the students through a few key sentences, dissecting how word choice could imply more than simple meaning; students began to understand the subtleties of language such as positive or negative connotation or the way a word might insinuate other meanings in context. They also explored how their own history, experience, and perspective might influence their word choice.

The biggest benefit of the lesson is its replicability, Whiting says. “The same people can do it over again with a different text and continue to learn about themselves and how their unconscious and implicit biases affect their worldview, slowly stripping out ingrained habits of bias confirmation.” For teachers who want to develop their own fill-in-the-blank exercises, The New York Times Room for Debate section—where Whiting sourced her exercise—features a variety of essays on a wide range of topics.