3 Ways to Plan for Diverse Learners: What Teachers Do

Every teacher already has the tools to differentiate in powerful ways for all learners.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.In The Wizard of Oz, Dorothy and crew are so intimidated by the Wizard’s enigmatic personality that they struggle to talk with him on equal footing. Fear and frustration overwhelm them as they blindly accept a suicide mission to slay the Witch of the West. In return, they each receive a treasured prize: a heart, a brain, courage, and a way home. Ironically, they already have these gifts—which they only discover after unveiling the man behind the curtain posing as the grumpy wizard.

Differentiated instruction (DI) casts a spell on educators as to how it meets all students’ needs. The skill set required to differentiate seems mystical to some and incomprehensible to others in this environment of state standards and high-stakes tests. Where does one find the time? The reality is that every teacher already has the tools to differentiate in powerful ways for all learners. I address some of these elements, such as assessment fog, in other Edutopia posts.

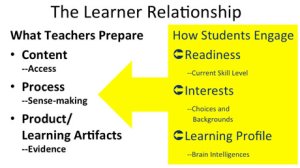

The DI elements were first introduced to me in How to Differentiate Instruction in Mixed-Ability Classrooms by Carol Tomlinson, and my understanding later deepened thanks to my friend and mentor Dr. Susan Allan. The core of differentiation is a relationship between teachers and students. The teacher’s responsibility is connecting content, process, and product. Students respond to learning based on readiness, interests, and learning profile. In this post, we’ll explore the teacher’s role for effective planning of DI, and in the next three posts, we’ll look at how students respond.

Content, process, and product are what teachers address all the time during lesson planning and instruction. These are the areas where teachers have tremendous experience in everything from lesson planning to assessment. Once the curtain is removed for how these three areas can be differentiated, meeting students’ diverse needs becomes obvious and easy to do—because it’s always been present.

Differentiating Content

Content comprises the knowledge, concepts, and skills that students need to learn based on the curriculum. Differentiating content includes using various delivery formats such as video, readings, lectures, or audio. Content may be chunked, shared through graphic organizers, addressed through jigsaw groups, or used to provide different techniques for solving equations. Students may have opportunities to choose their content focus based on interests.

For example, in a lesson on fractions, students could:

- Watch an overview video from Khan Academy.

- Complete a Frayer Model for academic vocabulary, such as denominator and numerator.

- Watch and discuss a demonstration of fractions via cutting a cake.

- Eat the cake.

This example should reassure teachers that differentiation could occur in whole groups. If we provide a variety of ways to explore the content outcomes, learners find different ways to connect.

Differentiating Process

Process is how students make sense of the content. They need time to reflect on and digest the learning activities before moving on to the next segment of a lesson. Think of a workshop or course where, by the end of the session, you felt filled to bursting with information, perhaps even overwhelmed. Processing helps students assess what they do and don’t understand. It’s also a formative assessment opportunity for teachers to monitor students’ progress.

For example, having one or two processing experiences for every 30 minutes of instruction alleviates feelings of content saturation. Reflection is a powerful skill that is developed during processing experiences. Some strategies include:

- Think-Pair-Share

- Journaling

- Partner talk

- Save the Last Word (PDF)

- Literature Circles (which also support content differentiation)

Of these three DI elements, process experiences are least used. Start with any of the shared strategies, and see long-term positive effects on learning.

Differentiating Product

Product differentiation is probably the most common form of differentiation.

- Teachers give choices where students pick from formats.

- Students propose their own designs.

Products may range in complexity to align to a respectful level for each student. (I discuss readiness in another post.) The key to product options is having clear academic criteria that students understand. When products are cleanly aligned to learning targets, student voice and choice flourish, while ensuring that significant content is addressed.

For example, one of my favorite practices is providing three or four choices in products. All but the last choice are predeveloped for students who want a complete picture of what needs to be done. The last choice is open-ended, a blank check. Students craft a different product idea and propose it to the teacher. They have to show how their product option will address the academic criteria. The teacher may approve the proposal as is or ask for revisions. If the proposal is too off-focus, the students work on developing a new idea. If they can’t come up with an approved proposal by a set due date, they have to choose from one of the predetermined products.

Reach Higher

Content, process, and product are key elements in lesson design. Fortunately, educators have many instructional tools that can differentiate these core areas of instruction, such as these 50+ social media tools, which set the stage for students to respond through the next three DI elements in this series:

I do an activity where I ask participants to stand and reach as high as they can. Then I ask them to reach even higher. They do. When considering your students’ needs, reach even higher in your practice—that extra stretch is inside us all—and students will benefit.