What Fact-Checkers Know About Media Literacy—and Students Should, Too

Professional fact-checkers use a strategy that’s at odds with how we usually teach information literacy. Here’s how to pass it on to your students.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.It’s news that’s all too real: We’re drowning in a stream of misinformation. The problem is so acute that the World Health Organization recently declared it an infodemic—a deliberate effort to spread misinformation, resulting in polarized public debate and amplified hate speech that threatens “long-term prospects for advancing democracy, human rights, and social cohesion,” the organization warned in a 2020 release.

In classrooms across America, a generation of new readers—digital natives who spend more than seven hours online every day and gather information from social media sites like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube—are struggling to parse fact from fiction. In a 2016 study, for example, researchers gave middle school through college-age students 56 tasks—ranging from evaluating the trustworthiness of a source to distinguishing the difference between a news article and an opinion column. “Overall, young people’s ability to reason about information on the internet can be summed up in one word: bleak,” the researchers concluded.

For educators, teaching kids to be critical media consumers can feel like a daunting—and unfair—responsibility, given the unrelenting flow of information that kids are subjected to daily. Still, a number of states are exploring how to address media literacy in schools, and nonprofit organizations like the News Literacy Project offer news literacy training for educators.

A fundamental problem, says Sam Wineburg, a professor of education at Stanford and the lead researcher on the 2016 study, in an interview with Edutopia, is that typical approaches to teaching information literacy are often outdated. In a holdover from the days of traditional print news, we often teach a vertical analysis of information: closely reading an article to look for mistakes, dubious assertions, or inconsistencies. “We learn to think critically by paying close attention and reading thoroughly from top to bottom, thinking very carefully about what we’re reading,” says Wineburg, whose body of research over the last three decades has focused on how students judge the credibility of online information.

But poring over a text with a fine-toothed comb from start to finish is time-consuming and inefficient, and few readers are knowledgeable enough to suss out factual errors. Instead, Wineburg offers a simple, teachable strategy, drawing from what he calls the “virtuosos of the internet”: professional fact-checkers.

In contrast to typical readers, fact-checkers move laterally rather than vertically, opening multiple browser tabs to validate claims and checking who is behind a site before continuing to read the initial page. They recognize that they’re at a disadvantage if they stay within a website, so they cross-check information across many sites to get a second—or even a third, fourth, and fifth—opinion. It’s a modern approach to identifying misinformation online that Wineburg says should be much more commonplace in schools.

Can Students Vet Information Like Experts?

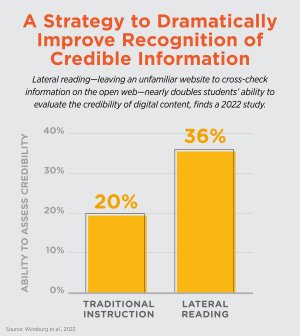

In a 2022 study, Wineburg and his colleagues set out to determine whether they could teach kids to read laterally—like fact-checkers—and whether there would be a change in student skepticism about sources.

Using materials they developed at the Stanford History Education Group, they asked 499 high school students to evaluate information found online. In one activity, students assessed the credibility of minimumwage.com, a “site purporting to offer nonpartisan information about minimum wage policy.” To get full credit, the students had to avoid being deceived by the site’s superficial qualities—that it was a dot-org, referenced scientific studies, and claimed it was staffed by professionals with advanced degrees—and find information about the organization behind the site, any hidden motives or agendas, and any other sources that might challenge the site’s claims.

Half of the students were given six 50-minute lessons in lateral reading, while the other half participated in their business-as-usual government classes. After a three-month period, both groups of students were tested on their ability to assess the credibility of a site, the accuracy of the information presented, and whether or not the claims made were supported by evidence. While students in the traditional government classes saw a modest gain of 25 percent, students who were taught the lateral reading strategy nearly doubled their scores, improving their eye for unreliable information by 71 percent.

“Students are bringing analog strategies to a medium that demands a digital way of evaluating information,” Wineburg concludes. To keep up with today’s ever-changing digital landscape, we need to adapt how we teach information and media literacy in schools.

A Different Way to Navigate the Web

At the heart of lateral reading is the idea that a single source of information should always be read with a critical eye. Instead of taking an article at face value, we should take a step back, says Wineburg, and think about the information it contains as part of a broader ecosystem of both reliable and unreliable sources: Is the claim corroborated by any other sources? Are we looking at firsthand accounts, or does the information originate elsewhere? What is the site’s reputation?

Media bias and reliability charts can help readers quickly identify where a major publisher lies on the political divide and how accurate its reporting is—from Slate and The New York Times to The Economist and The Wall Street Journal to Breitbart News—while fact-checking sites like PolitiFact.com, FactCheck.org, and The Washington Post Fact Checker can be used to help quickly verify a claim.

Developing a list of reputable sites and cultivating a skeptical mindset in students—information should be considered dubious until verified—should be central to how students vet information they read online. Meanwhile, a quick scan for spelling or grammatical errors, sensational claims that sound too good to be true, and overtly political perspectives and single-source reporting, along with Google searches about the site itself, can also help students identify possible misinformation on an unknown webpage.

While researching, students shouldn’t spend too much time on any one site, Wineburg asserts. Unlike many readers, expert fact-checkers are adept at ignoring information while looking for answers; they almost immediately leave the site of the original claim and move laterally across the computer screen as they open new web pages. They assume that information is low-quality until fundamental questions are answered: Does a quick search on Google yield information about a website or news article that will help me gauge its trustworthiness? Have journalists investigated the site in question and uncovered a flow of funds from organizations that have a hidden agenda? Are the website’s claims confirmed by reputable sites in the cascading tabs?

Getting Started in the Classroom

Here are five tips for setting kids up to succeed at lateral reading, drawn from our own research and Wineburg’s work—and there are more on the Stanford History Education Group’s website.

1. Guide students with probing questions. U.S. history teacher Will Colglazier, who is part of the Stanford History Education Group team, launches a lesson on lateral reading by asking his students to answer three key questions when assessing the credibility of a website:

- Who is behind the information? Students should investigate the people making the claims and how their motives could influence what is presented and suppressed.

- What is the actual evidence for the claim? Claims often appear to be scientific or based on evidence; when students gather and assess the actual evidence, does it still add up?

- What do other sources say? Students should corroborate claims and verify information with other sources, such as experts, scholarly journals, and reputable news sites.

2. It’s OK to use Wikipedia. Students are often told, “Don’t go to Wikipedia,” says Wineburg. Yet “one of the first things fact-checkers did was go to Wikipedia and use it as a jumping-off point, as a portal to more authoritative sources,” he says. In fact, reading a Wikipedia article “can provide students with an opportunity to learn about peer review, sourcing, footnotes, and internet research,” explains Benjamin Barbour, a high school history and government teacher in Fairview, Pennsylvania.

Meanwhile, it’s a myth that anyone can change what’s written on a Wikipedia page. Try changing Donald Trump’s Wikipedia page, says Wineburg. “Unless you are the highest-badge Wikipedian, you’re not going to be able to touch that page.”

3. Work on productive skimming. “You don’t have to read everything on a particular website to make a decision,” says Wineburg. It’s difficult, if not impossible, to spot misinformation on the basis of the original source’s claim. Instead, get a quick sense of the content by scanning the page, and then do a Google search and open more sites to see if the information is supported by other sources. Come back to your original page for deeper reading after assessing the claims more broadly.

4. Don’t be fooled by appearances. Twenty years ago, creating a professional website was costly; a poorly designed site peppered with spelling errors, clip art, and inconsistent formatting was often a red flag. Today, however, slick websites are more attainable and affordable. Just because a site looks professional doesn’t mean it’s trustworthy.

Similarly, it’s easier than ever to purchase .org and .com domain names, and using those suffixes to determine a site’s reliability is a mistake that students often make.

5. Create a list of go-to sources. Engage in a conversation with students about how to develop a roster of reputable, go-to sites—trusted resources from across the political spectrum from The Wall Street Journal to The New York Times, government agencies such as the FDA and the EPA, and independent research organizations like the National Science Foundation and NASA, for example. As part of the conversation, talk about bad-faith outliers on both sides of the political divide, like Daily Kos and Breitbart News, and explain why relying on reputable, well-established publications is a critical part of smart media literacy.