How Novice and Expert Teachers Approach Classroom Management Differently

A 2021 study reveals the ways in which new and experienced teachers think about discipline—plus 6 takeaways for managing your classroom effectively this year.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Good classroom management is mostly invisible. While outbursts and disruptions are inevitable in the course of an academic year, they can be kept to a minimum by employing subtle techniques that work behind the scenes to create a positive classroom culture.

Understandably, there’s a significant gap between how novice and expert teachers approach classroom management—one that can take years of experience and training to fill, according to a new study. And while there’s no replacement for spending time in the classroom, an awareness of the right strategies, and the right mindsets, can put new teachers on the fast track to adopting tactics that work but might feel counterintuitive or risky. Meanwhile, more experienced teachers can benefit from insights that may help them sharpen or extend their existing playbook.

In the study, researchers asked 39 novice and expert teachers—school leaders and mentors in charge of training new teachers—to watch video clips of a high school classroom. In each video, an educator could be observed giving instructions or walking through the class while students worked. During each video, a disruptive event would occur, ranging from students talking loudly to students refusing to participate in the lesson. The teachers in the study provided feedback on the events in the classroom, critiqued the observed teacher’s own classroom management strategies, and offered their own solutions.

Here’s how expert teachers approached classroom management—plus six teacher-tested strategies to make changes in your own classroom this year.

SEEING THE BIG PICTURE

While both novice and expert teachers relied on reactive strategies to address student misbehavior—for example, by giving a reprimand like “Eyes on me!” if students were being disruptive—expert teachers were far more likely to consider how proactive strategies could have prevented the misbehavior in the first place.

New teachers tended to view classroom management narrowly, as a way to respond directly to disciplinary problems, while expert teachers had a “more comprehensive understanding of classroom management and its complexity,” the researchers found—conceiving of discipline in the broader context of how lessons were organized and executed, how clearly the teacher communicated expectations, and even how the physical environment was arranged.

SEEKING ROOT CAUSES

Expert teachers were more adept at interpreting the causes and influences behind student behavior. If students weren’t paying attention, for example, inexperienced teachers were more likely to focus solely on correcting behavior, while expert teachers entertained the idea that the behaviors were situational and sought strategies to improve the learning environment to short-circuit future disruptions.

Compared with novice teachers, experienced teachers tended to have a “more elaborate and interconnected” understanding of student misbehavior, forming a holistic picture of their students.

STRIKING THE RIGHT BALANCE BETWEEN AUTHORITY AND AUTONOMY

Establishing a set of rules and then demanding compliance doesn’t work, especially with older students. Eventually, expert teachers come to see the classroom as an ecosystem involving a delicate balance between teacher authority and student autonomy. “They viewed student behavior in the context of teacher behavior, thinking about reasons and solutions” instead of overemphasizing “order and discipline.”

Sometimes when students act out they are merely exhibiting normal, healthy developmental behaviors. For the most experienced teachers, a healthy classroom is one in which students are allowed some reasonable leeway in their behaviors and are taught how to think of others and regulate themselves.

FINDING YOUR PLACE AND TONE

All teachers made efforts to monitor the room, but expert teachers were more proficient, often because they also had greater positional awareness, making sure that they occupied locations where students—and student work—would be in view. For example, one teacher noted that he frequently “walks through the rows and looks at what they (students) are doing”—a common strategy to ensure that students are on task when doing independent work.

Expert teachers were also mindful of how their body language, facial expressions, presence, and ability to control their own emotions affected the emotional state of their students.

“Emotions are contagious, and when a teacher is able to model a calm presence through their tone, facial expression, and posture, students are less likely to react defensively,” writes Lori Desautels, a professor of education at Butler University. Work to project enthusiasm, and try to keep cool if at all possible.

GETTING ADAPTIVE

“Successful classroom management requires the adaptive application of a repertoire of different strategies,” the researchers explain. If a student is acting out because they’re having a bad day, that’s going to require a different approach than if they’re frustrated by the difficulty of a lesson or are confused by the instructions—researchers discovered that the latter issues account for 20 percent of classroom misbehavior, according to a separate 2018 study.

As teachers become more experienced, they undergo a “shift in perspective” from “seeing parts versus seeing the whole,” the researchers report. While novice teachers relied more on routines and consequences, essentially following a script when it came to managing students’ behavior, expert teachers had “adaptive expertise” that allowed them to draw from a variety of strategies depending on the context.

TIPS FOR TEACHERS

1. Plan your environment. Your classroom plays a key role in shaping the behavior of your students. A 2018 study, for example, found that heavily decorated classrooms made it harder for students to focus on a lesson, leading to off-task or disruptive behavior. While certain visual elements of the classroom can support learning—anchor charts, maps, images of role models, and displays of student work, for example—an overabundance of decorations can overstimulate.

Seating plans also matter: A 2012 study found that students were three times more likely to be disruptive if they chose their own seat rather than being assigned one. If you’re going to offer seating choice—many teachers say it ultimately improves classroom behavior—consider doing so only situationally, and provide clear rules to let students know the consequences of frequent misbehavior.

2. Co-create norms. A common classroom management mistake is to display a list of rules and expect compliance. It can be more productive to have a conversation with your students about the reasons why rules exist, and then produce a set of governing principles by consensus. In California, high school English teacher David Tow instills a sense of shared responsibility and ownership over the classroom’s civility by co-creating classroom norms with his students. Together, they identify guidelines like being respectful of others, and then they evaluate the guidelines’ feasibility throughout the year, discarding the ones that don’t seem valuable, meaningful, or useful.

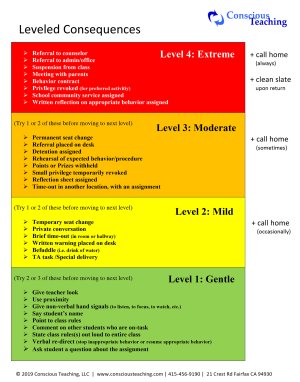

3. It’s not one size fits all. Find ways to measure the size of the problem, and respond accordingly. When a student misbehaves, Grace Dearborn, a high school teacher and the author of Conscious Classroom Management, has developed a series of tiered choices framed “as consequences, not punishments” to give students more autonomy. For example, low-level misbehavior might receive a “gentle” response, such as using nonverbal hand signals to encourage students to pay attention, or Dearborn might try “drive-by discipline,” like saying the child’s name quickly to disrupt the behavior without getting drawn into a bigger battle.

Consequences are clear to the students and increase in intensity if the misbehavior persists: Students may be asked to change seats or take a time-out to reflect on their actions. Ultimately, the most severe consequences—detention or a meeting with parents—are used if the student’s behavior doesn’t change.

4. Consider what’s unspoken. Nonverbal communication like eye contact, body language, and even how you position yourself in the room has an impact on student behavior.

“Presence is crucial to maintaining classroom management and to effective delivery of instruction, and it’s a skill we can develop with effort,” explains Sol Henik, a high school teacher. Develop your teaching presence—you can record yourself while you’re teaching or solicit advice from trusted colleagues—circulate in areas where you can see and be seen, and make productive use of eye contact, not as a tool for surveillance but as a way to connect with your students, project confidence and accessibility, and build rapport.

5. Relationships, relationships, relationships. Ultimately, classroom management begins and ends with strong relationships. A 2018 study found that greeting students at the door set a positive tone for the rest of the day—for example, dramatically improving academic engagement and behavior. Another study concluded that engaging in prosocial activities throughout the school year—such as regular check-ins or morning meetings—can reduce disruptions by up to 75 percent.

Finally, learning a little about students’ personal lives through get-to-know-you surveys and identity activities can provide insights into the root causes of behavior. Students can draw their own “identity portraits” to share both visible and invisible details about themselves, like religion, ethnicity, or the hobbies they enjoy. You can also use writing prompts like “What inspires you?” or “What dreams do you have for after high school?” to mine information you can use to deepen relationships and connect classroom lessons to students’ interests.

6. Pick your battles (but do battle when you have to). Students who are frequently the target of negative attention—being called out if they’re not paying attention or are chatting with another student, for example—are more likely to become disengaged and apathetic, which leads to more behavioral issues in the future, according to a 2016 study. Don’t try to fix all misbehavior in your classroom—pick your battles, avoid escalating the situation if you can, and remember that the most effective classroom management strategies are based on building relationships and increasing engagement with the content.