3 Schools, 3 Principals, 3 Cell Phone Bans

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Recently, 16-year-old sophomore Olivia walked into Principal Matteo Doddo’s office to deliver a piece of unexpected news: “I got more work done today than I’ve gotten done for the last two weeks,” she said, surprising even herself. “I didn’t have to worry about my cell phone.”

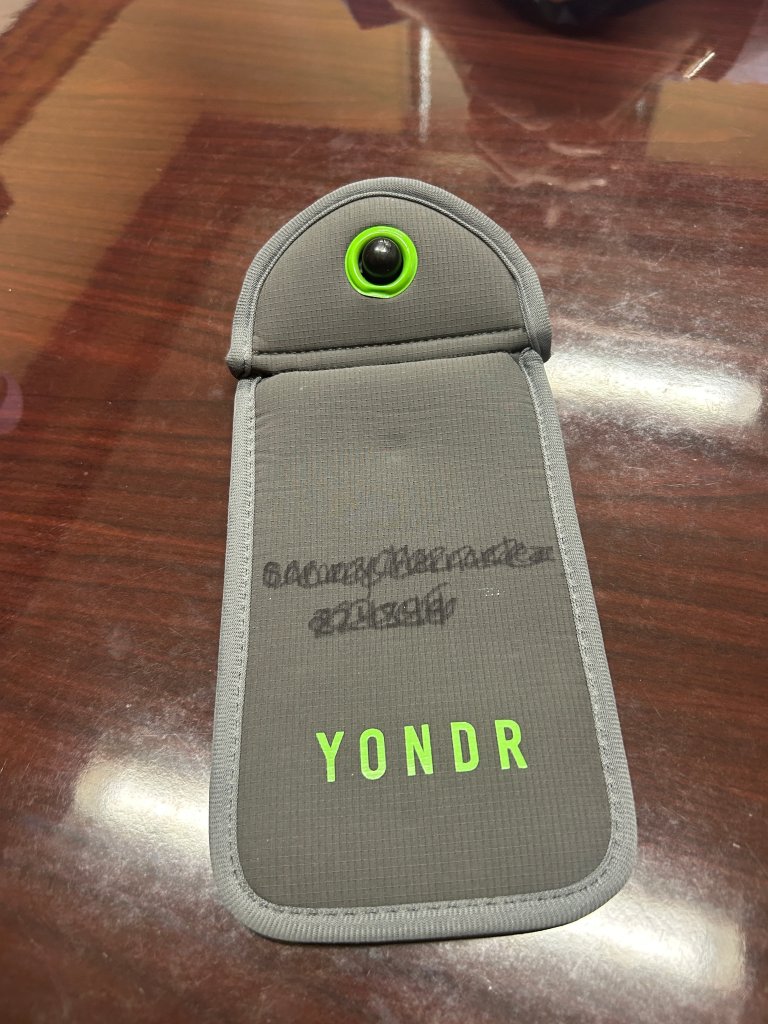

Only 24 hours prior, as the school approached the start date of its restrictive new phone policy, the same student was standing in front of him experiencing something like a panic attack. The sight of an empty Yondr pouch sitting on the large wooden table in his office had set Olivia’s nerves alight. Yondr representatives, who market the lockable receptacles as a “patented system to create phone-free spaces,” had warned Doddo that this was inevitable: For some kids, locking their phones away was going to be traumatic, at least initially. That anticipatory Monday, Olivia’s hand trembled as she hovered her phone over the pouch to see if it would fit inside, keeping a safe distance almost out of fear that “it was going to bite her,” Doddo recalls.

But the next day, despite her nerves, Olivia and 900 other ninth- to 12th-grade students at Newburgh Free Academy’s North Campus in Newburgh, New York, stored their phones in Yondr pouches for the duration of the school day. In a month’s time, 2,200 other students at the school’s main campus would follow suit.

Doddo had his doubts about whether his students would, or even could, go without using their phones for a school day. “Now I know that they can do it,” he says, smiling. “It’s hard. Phones are addicting. But for the seven hours that they’re here, they’re actually doing it.”

Getting Things Under Control

It was a long time coming. Cell phones had been an academic distraction and a source of social drama at Doddo’s school for almost as long as they’d been in existence, and past policies had done little to rein them in. The school had previously required phones to be stored in lockers or bookbags during the day, but students consistently ignored the directive, sneaking phones into classes and bathrooms and circulating videos of staff and classmates taken without their consent.

It didn’t help matters that as students traversed the building on their bell schedules, tolerance for breaking the rules waxed and waned. Some teachers were strict: A large number of Newburgh’s disciplinary referrals in those days were related to use of electronic devices during instruction—and insubordination when students refused requests to put their phones away. Other educators grew tired of repeating the rules only to see them broken again and again.

For too many students, the risk of being caught is worth the reward. A 2016 study of technology use in college classrooms revealed that students spent more than a third of class time engaged in nonacademic activities like social media, texting, reading and writing emails, and even shopping or watching movies. Other studies point to a strong correlation between access to phones and mental health visits to counselors and psychologists. Cell phones can also put students’ creative thinking abilities in a straitjacket, according to research psychologist and educator Larry Rosen. Proximity to phones impacts “fluid intelligence, which allows you to think differently, to think creatively when trying to solve a problem, or let your mind sort of run free and find that creative spot,” Rosen explains.

What intrigued Doddo about Yondr was that it closed so many enforcement loopholes. Now, as 900 students pour into the school building through two entrances every morning, a handful of staff members watch them put their phone in a Yondr pouch, tap it against a magnetic hub that locks the pouch, and then place the pouch in their backpack. Students won’t access their phones again until the end of the school day, not even at lunch. A forgotten, lost, or damaged pouch requires students to fill out a paper slip with their name, student ID number, and reason for the noncompliance. The paper is then attached to the phone with a rubber band, and placed in a basket headed to the main office, where it can be retrieved at the end of the day.

Despite the size of the operation, the process is surprisingly swift. It takes about 35 minutes, from the arrival of the first bus at 6:35 a.m. to the start of first period at 7:10 a.m.

Pulling the Band-Aid off was difficult, Doddo admits, but pushback has been minimal, and classroom distractions have plummeted: “From day one, [teachers and other staff] made a point to let us know, ‘this has made such a difference in my classroom. [Students] are paying attention. They have their hands up. They’re more engaged.’” In Carrie Maiale’s ninth-grade English classroom, you could hear a pin drop during silent reading, as students stayed focused on an older, slower kind of medium—despite the principal and a journalist entering unexpectedly.

Most importantly, Yondr pouches relieved a source of constant tension between students and teachers: “At the end of the day, there’s no gray area with this—the phone is either in the pouch and turned off or it’s not,” Doddo said.

One policy won't rule them all

In Danbury, Connecticut, middle school Principal Kristy Zaleta was struggling. There’s a certain amount of conflict and crying that comes with supervising hundreds of 12- and 13-year-olds—she understood and accepted that—but post-pandemic behavior among her kids was unlike anything she’d seen in her 20 years as an educator: multiple fights and daily destruction of property. “It was just this mob mentality,” she says. “‘Oh, there might be a fight?’ Suddenly they’re all running; there was even a girl on crutches hustling over to try to see.”

The phone policy in place at the time, which gave teachers broad latitude to set guidelines within their classrooms, was at the center of a lot of the problems. “Time after time, our investigations led us to student-posted videos taken during school, inflammatory texts that occurred both during class and when students left to use the bathroom, and social media posts that encouraged violence and property damage as if it were a game,” Zaleta writes in Principal Leadership.

Yondr pouches were considered, but the cost—$25 to $30 dollars per student—combined with cautionary tales of students smashing the magnetic closure and destroying pouches, deterred her. Zaleta and her two assistant principals turned to parents, teachers, and kids to take the community’s temperature. The overwhelming majority were in agreement, including the kids: A new policy would go into effect at Rogers Park Middle School prohibiting cell phone use entirely during instruction.

Unlike Doddo’s school, teachers ultimately decide what enforcement looks like inside their classrooms, as long as the policy’s underlying restrictions aren’t violated. A few educators, like seventh-grade math teacher Grace McKinley and eighth-grade American History teacher Joe Barata, use hanging cell phone caddies purchased by the school, while others require students to store their phones securely out of sight. Sixth-grade ELA teacher Avery Rourke used the caddies at first—students slide phones into pockets, which hang from the wall like a display case—but found them to be an alternative source of distraction. “You had students that were a little bit self-conscious that they didn’t have the newest iPhone,” she says.

Students are allowed to use their phones at lunch, and briefly during transitions to check their schedules. Although cyberbullying during the day could reassert itself, it hasn’t been a problem at Rogers Park so far. Zaleta hopes the time students could spend in the lunchroom huddled together typing cruel messages is funneled into an alternative outlet: recess. Students have always been allowed to go outside after they eat, but she’s hoping that reducing their access to phones during the day leads to more social engagement and a lot more play.

Overall, the tenor of the building has changed considerably. “In combination with not always using computers in class, we’re seeing more peer-to-peer conversations,” Zaleta says, explaining that the school has chosen to emphasize more human-centered teaching approaches. “We’re seeing kids engage more in classrooms. Do they want to learn about math? Not all the time. But they’re not distracted by something that’s buzzing in their pocket.”

Buy-In TAKES PLANNING

As Principal Todd Chandler considered a cell phone policy for his middle school in Luxemburg, Wisconsin, he decided he wanted the whole community—and especially the kids—to acknowledge and solve the problem together. “The biggest thing to me is that they all understand why we’re doing this,” he said.

This year, the school piloted having students keep their phones "away for the day," in their lockers from the first bell of the day to the last. Buy-in would take time, so Chandler slated the transition to begin over the summer. He talked with staff and parents to gauge levels of support, made himself available for informational sessions where people could ask questions, and set up optional screenings and discussions of the film Screenagers: Growing Up in the Digital Age—a documentary exploring how adults can better help children find balance in their technology use.

At Luxemburg-Casco Middle School’s new student orientation, incoming seventh graders and new eighth graders were introduced to the policy, and teachers began the school year with a review of new expectations, processes, and procedures.

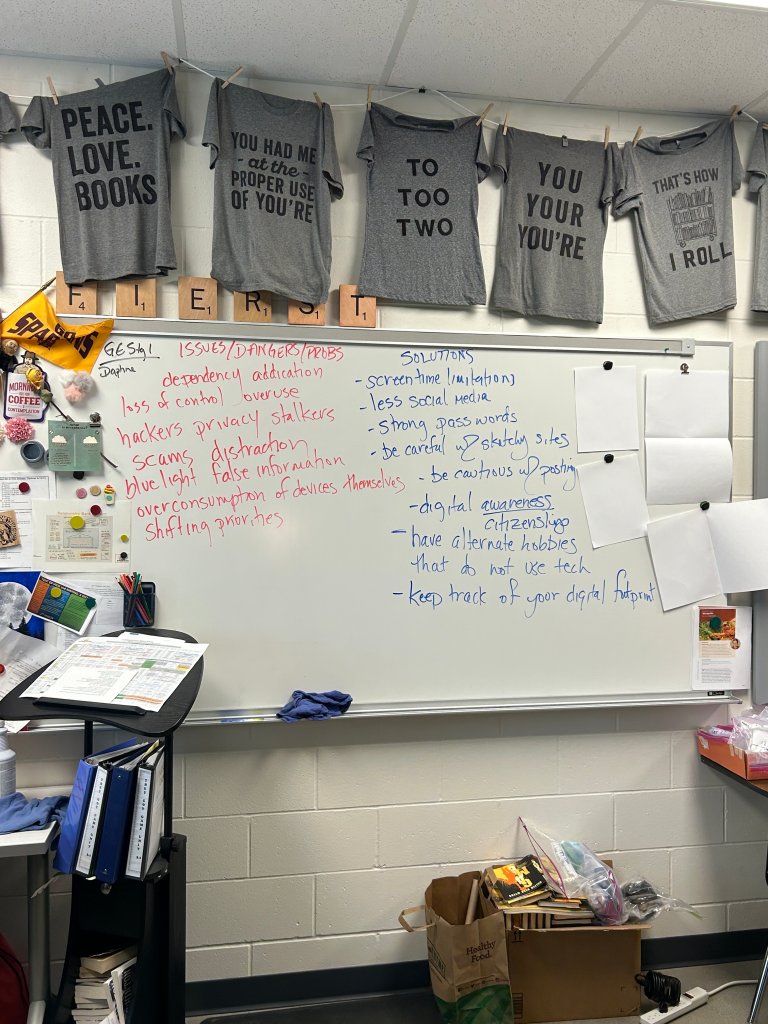

In some classes, students get an opportunity to explore their relationships to cell phones. In Pam Fierst’s eighth-grade ELA classroom, a bellringer activity poses a question about the possible downsides of digital technologies. Students highlight many of the issues adults worry they’re unaware of: dependency or addiction, loss of control, hackers and stalkers, scams, distraction, and false information. Their ideas for solutions include limitations on screen time, less access to social media, stronger passwords, and alternative hobbies that don’t rely on technology.

Back on the East Coast, Doddo took a similarly long-term approach. A letter sent over the summer dipped a first toe in the water, introducing the idea of the policy, with more details to come. Long before the letters had been sent, school psychologist and intervention specialist Robin Mojica was already pushing into classrooms to talk to students about the impact of phones on the brain, social development, and the body’s stress response. Kids found those chats informative, Mojica says, so the discussions led to school-wide restorative circles about how phones make them feel: Once in September and once in October, before the November rollout of the new policy, the entire North campus building stopped at third period to initiate the conversations—circles formed everywhere, from the lunchroom to the gym.

During the first few days of Yondr implementation, several students came by Doddo’s office, visibly anxious about not being able to reach their families. Doddo and his staff tried to create reasonable options, without giving up on the broader principle: Students can use the main office phone if they need to call their parents, and—on a case-by-case basis—there’s a magnet in his office that unlocks the pouch so kids can text or call from their cell phone.

You can run, but you can't hide

Hallways at Newburgh Free Academy are filled with the hum of student chatter again, Doddo says, and kids move briskly between classes without the familiar hunched postures of the school’s cell phone era. Teachers say that for struggling students, in particular, the change has given them space to turn things around and start passing classes again. The policy is still in its infancy at Newburgh, and while it won’t be possible to pinpoint the impact on state assessment data, eventually Doddo would like to be able to tie the policy more firmly to academic outcomes.

But disengagement in school precedes cell phones, and Doddo’s students, like students everywhere, can always fall back on old habits like passing notes, doodling, or simply staring out the window.

At a New York City school that recently introduced Yondr pouches, a simple request for students to form groups for discussion receives blank stares—students sit there, silent passengers on a bus whose route or even final destination they don’t care to know. Zaleta and her staff, though, see the bigger issue and say they are ready to take on the challenge. “We've spent a lot of time not just on the rules around cell phones, but on how we engage with kids, the strategies teachers are using to make more student-to-student conversations happen,” she insists. “How can we hook them with something that’s engaging?”

Being a principal today is a very different job than it was six years ago, Doddo agrees. He continues to level-set for himself and his staff: Cell phones are gone, but the battle for students’ minds is not yet won. “We’re proud to say that this has worked, but we also know that we have to be realistic about what didn’t work,” he explains. “We’re human beings coexisting in one building of over a thousand people; things happen and we have to be prepared for that. But I’m proud of the fact that we are all doing this together.”