7 Ways to Teach Kids to Manage Their Own Conflicts

Strengthening students’ capacity to evaluate their problems and consider a number of solutions leads to better, less impulsive conflict resolution.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Whether it’s a dispute over who is out during a heated game on the playground or a deeper clash of values or personalities, any educator knows that conflict between students is normal inside and outside of the classroom.

Assisting students in resolving conflicts with peers is an important aspect of classroom management—but solving the problem for students, rather than assisting students in resolving problems on their own, can prevent the development of vital conflict-resolution and problem-solving skills.

Equipping children with these skills as early as possible is crucial and key to their interpersonal success moving forward, explains Carolyn Coffey, a preschool teacher at Educare New Orleans.

“We’re teaching them the right way to respond to conflicts, to use self-control and calm themselves,” she says. “If we wait until they get to fourth grade or even middle school, they’ve already learned in practice what they’re going to do in order to resolve something… and it might not be the best way.”

Many teachers like Coffey have found creative ways to help students identify big emotions, self-regulate, and resolve interpersonal conflicts on their own. We asked educators to share what these activities look like in their classrooms.

1. How big is my problem?: To help children understand the different sizes of problems they may encounter, including how to assess conflicts with other children, teachers at Lister Elementary School in Tacoma, Washington, have students think proportionally about their emotions.

Students actively discuss the kinds of issues they face and also fill out a big versus little problems worksheet using real-life examples. Different types of problems are written down on pieces of paper—from losing your homework to a relative being in the hospital—and students place them into categories based on the size.

“We talked about the different sizes of problems, going from one being the smallest up to five being something that’s major that affects lots of people and takes a long time to solve,” says fourth-grade teacher Anna Parker. “If I start throwing things and screaming because someone took my pencil, that is an unexpected behavior based on the size of that problem.”

2. A pathway to peace: At elementary schools in the Modesto City School District, students can utilize a six-step Peace Path to navigate their own conflicts. The actual path is generally spray-painted or hand-painted onto an asphalt concrete surface with markings for where each student can place their feet. While standing across from each other on opposite sides of the path, students progress through the path answering a sequence of questions aloud: What is the problem? How do you feel? How do you think the other party feels? Collaboratively, with adult supervision, students discuss solutions and agree on a plan to move forward amicably.

“At the elementary level, problems can exist anywhere,” says Associate Superintendent of Student Support Services Mark Herbst. “In situations where [students] need to engage in problem-solving, they will go to the Peace Path, and in some cases—depending on the students and [their familiarity] with the process—they’re asked to do it independently.”

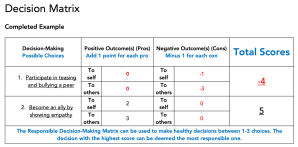

3. Pros and cons, 2.0: Bolstering students’ ability to assess their options and examine a range of alternatives—and possible consequences—leads to better, less impulsive choices while navigating conflicts.

Filling out a decision matrix helps students model empathic thinking, providing them with a framework to think about the costs and benefits of their behavior. “Students can weigh options and evaluate the impact (pros and cons) on themselves and others using a simple point system, with positive numbers for pros and negative ones for cons,” educational coach Jorge Valenzuela explains.

For example: a student may face a decision about teasing a classmate, determining whether to be an ally to the victim or participate in the bullying. If the student can’t see any positive outcomes to a course of action, it receives zero points. The student then looks at possible negative outcomes for the action—like hurt feelings or punitive consequences for anyone involved—and subtracts one point for each.

“After tallying their numbers, the decision with the highest score can be deemed the most responsible one,” Valenzuela says. While an actual decision matrix is not always handy when on the playground, the method, once learned, can be quickly used to assess the options in a potential conflict.

4. Turning problems into opportunities: At the beginning of class, eighth-grade English teacher Cathleen Beachboard has her students write down a problem or issue they are having on a sticky note. While the strategy can be used for any type of issue—academic or interpersonal—it’s applicable to conflict management as well. After being paired with a classmate, each student has one minute to talk about their problem, and their assigned partner can make suggestions on how to solve it.

Students participate in this activity every three to four weeks to help relieve their stress and practice problem-solving. Beachboard says it also shows students that she cares about their well-being and “allows students to see that sometimes you have to go to others with problems for a new perspective.”

5. Practicing conflict: Engaging students with hypothetical conflict scenarios or group role-playing provides them with an opportunity to practice their response to real-life conflict. They can weigh the benefits and drawbacks of each option before they make a choice, says English teacher Sean Cooke, and do so in a low-stakes environment. An additional benefit: Students gain an appreciation for the opinions of their peers and are pushed to be more creative in determining how to best solve a problem they may face.

“By seeing others model thinking that differs from their own but that leads to a solution which satisfies their own interests, students learn to accept that there is more than one way to skin a cat, so to speak,” he says.

6. A shift in perspective: Educator Neil Finney asks, “if you were me (the teacher), how would you handle this?” to facilitate conversations between students that, he says, produce longer-lasting resolutions to conflicts.

“Seeing the issue from an outside perspective, in this case through the eyes of the teacher, can allow the student to temporarily disassociate from her own behavior choice,” he says.

Asking students to talk through the thinking of another—a practice called scripted empathy— may result in an awkward silence at first, but Finney counsels patience, suggesting that teachers wait at least 10 seconds for students to process the question, employ their empathy, and construct a response.

7. A little help from my friends: At Mid-Pacific Elementary School in Hawaii, fifth-grade students are trained in the art of peer mediation. Then, as part of the Peace Team, they’re available to help third- and fourth-graders mediate problems that arise on the school campus. If a member of the Peace Team sees a potential conflict, they will approach the students and ask if they’d like to go to peer mediation. Students can also request peer mediation as long as all parties are willing to engage.

Students are escorted to a quiet area on campus set aside for these conversations, and under adult supervision the resolution process begins. This can sometimes take a few minutes or spread out over the course of several days, depending on the conflict, says Principal Edna Hussey. Two students arguing over an “unfair call” in a playground game of Four Square, for example, could agree that a redo would be a simple solution.