4 Ways to Fight Bias in Grading

Unconscious bias may be unavoidable, but here’s how you can reduce its destructive impact.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.We are all subject to implicit bias, the research says, in spite of our best efforts to prevent it. Asian and Black job applicants who “mask” their race on résumés get more callbacks. Black patients seeking medical treatment are consistently “undertreated for pain” compared with White patients. And when a job applicant’s weight is concealed, they’re perceived as more suitable for employment than heavier candidates.

In the classroom, decades of evidence confirm that teachers are not immune and that some degree of unconscious bias is often at play, especially in the absence of intentional measures to control it. Bias has a way of seeping through the smallest cracks, imperceptibly influencing the way we perceive students, compromising accuracy in grading, and even altering a wide range of educational outcomes.

An inaccurate grade may appear to be a temporary setback, but taken together across a child’s K–12 educational career, biases in grading can have lasting consequences, discouraging students by repeatedly sending the message that their best efforts don’t meet the mark, producing a ripple effect with far-reaching implications—from course placement to scholarships, college admissions, and even job opportunities.

There are ways to course-correct, says David Quinn, an assistant professor of education at the USC Rossier School of Education in a recent study. “The long-term goal is that we want to fundamentally change teachers’ attitudes because that can have downstream impacts on behaviors, and thus on students’ experiences. But we haven’t figured out how to do that yet,” Quinn tells Edutopia. “In the meantime, we need to significantly reduce the impact of those implicit biases.”

SAME SAMPLE, DIFFERENT GRADE

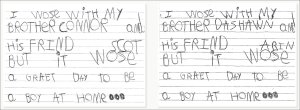

In the study, Quinn asked 1,549 preschool through 12th-grade teachers to evaluate two versions of a writing sample. The sample was a short personal narrative written by a fictional second-grade student who described a weekend spent with a sibling.

“The versions were identical in all but one aspect: each used different names for the brother to signal either a Black or a White student author,” Quinn wrote in an article for Education Next. “In one version, the student author refers to his brother as ‘Dashawn,’ signaling a Black author; in the other, his brother is called ‘Connor,’ signaling a White author.” Half the teachers were randomly assigned the Dashawn version, the other half got the Connor version, and they were asked to grade the work based on grade-level standards.

The differences in the writing samples were negligible, but the bias effect was striking: Overall, teachers were 4.7 percentage points less likely to score the “Dashawn” writing sample as meeting or exceeding grade level than the “Connor” sample, and that gap opened up to 8 percentage points for White teachers. Teachers of color, however, did not show obvious bias in the evaluation.

SLOW IT DOWN TO GET IT RIGHT

In classrooms, there are “opportunities all the time for teachers’ unconscious racial biases to come out, even when we think that they aren’t,” says Quinn, who taught third and fourth grade in North Las Vegas, Nevada, before moving to K–12 education policy research. “So encouraging teachers to reflect on that and be aware of it is the most important thing for students’ experiences.”

But there’s more that can be done to make assessment less prone to bias. A simple, low-cost tool is a well-formulated rubric in which grading criteria are laid out in advance, delineating for teachers exactly what criteria—including gradients within that criteria—they’ll use to assess student work. “Rubrics are a way of slowing down that thought process,” says Quinn. The point is to create a bulwark against “the automatic cognition that filters in and influences behavior.” By forcing a slow-down, the rubric allows teachers to “compare the work to the actual performance criteria. It’s an opportunity for the impact of the bias to be reduced, rather than simply acting on a gut reaction.”

In the study, when teachers rated the two writing samples using a rubric with specific grading criteria—which included standards such as: fails to recount an event, attempts to recount an event, recounts an event in some detail, or provides a well-elaborated recount of an event—instead of a general grade-level scale, the difference in grades was nearly eliminated.

GET A SECOND OPINION (AND A GOOD NIGHT’S SLEEP)

Another simple way to reduce bias is by having colleagues at times check each other’s work—in a quick weekly or biweekly check-in, for example, or in a regular professional learning community environment. “It may be working with grade-level colleagues to compare writing prompts, and to look at how teachers assessed those prompts based on the established rubric,” says Quinn. “There is good evidence that even just the awareness that people’s work will be reviewed for bias decreases the level of bias that is shown in the work.”

Middle school math teacher Jay Wamstead used a clipboard to keep track of his classroom management and conversations for one month, a focused effort “to check the spaces in my pedagogy where bias and prejudice were leaking through.” His list tracked his habits across areas like discipline, calling on raised hands and cold calling, and who he most often chatted or joked around with. “If you keep track of these aspects for a month, you may discover something surprising about the way you interact with students. I know I did,” Wamstead writes. “But it gave me something to work on, a plan to make, and an action item to fix. I know it’s only scratching the surface, but it gave me a place to begin.”

Finally, research shows that implicit bias tends to creep in when we’re tired, overworked, and stressed—factors that besiege many teachers’ professional lives. “We know that implicit bias has more of an influence on behavior when you’re under stress, when you are fatigued, or when there is some type of time constraint,” Quinn concludes. Becoming aware of this tendency during grading is helpful, but when schools genuinely commit to reducing those contextual factors—ensuring that teachers have enough time built into the schedule for evaluations, for example, and that they can do the work in an environment where they’re not distracted and pressured—it can make a real difference.